Aamna Mohdin

The Guardian / Februari 6, 2026

As Gaza’s crossings reopen only partially and displacement accelerates in the West Bank, claims of systematic domination are being made by human rights groups, legal scholars and former Israeli officials.

The Rafah crossing, a fragile lifeline for Gaza, has reopened.

But movement in and out of Gaza remains tightly controlled, with Israel determining who is permitted to leave or return. Of the roughly 4,000 patients with official referrals for medical treatment abroad, only a small fraction have been allowed to cross. Fewer still have been allowed back. Meanwhile, airstrikes continue, and more than 556 Palestinians have been killed since the ceasefire was signed last October.

In the West Bank, mass displacement of Palestinians is gathering pace, and the UN, along with Israeli soldiers and activists, warn that the Israeli army is increasingly entangled with settler violence, with reserve units drawn from settlements accused of operating as vigilante militias.

These are the day to day realities of Israel’s occupation of the Palestinian territories, now in its 58th year. Last week, prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu said Israel’s “security control” from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean would remain indefinitely.

For a growing number of legal experts, that amounts to apartheid. To understand that argument, I spoke to Jerusalem-based journalist Nathan Thrall, author of the Pulitzer Prize winning A Day in the Life of Abed Salama. That’s after the headlines.

‘This not stopping, it’s accelerating. It’s going on at the fastest pace ever’

When Israel declared statehood in 1948, it did so without formally defining its borders. After the 1967 war, Israel took control of more territory, occupying East Jerusalem, the West Bank and Gaza.

Across the world, these occupied territories are treated as the basis of a future Palestinian state, with Israel understood to exist within its pre-1967 borders.

But for the past 15 years, Nathan Thrall has sought to puncture what he sees as the central fiction produced by that framework: that Israel exists separately from East Jerusalem, Gaza and the occupied West Bank.

Thrall’s arguments have drawn sharp criticism from the Israeli right, which accuses him of misrepresenting Israel’s security needs and delegitimising the state. In 2023, an Israeli diplomat sought to persuade Bard College, where Thrall has taught, to cancel a course examining whether Israel practices apartheid in the Palestinian territories. The college declined.

But Thrall, who previously spent a decade at the International Crisis Group, as director of the Arab-Israeli Project says: “There is one sovereign state, it’s the state of Israel.” And that state, he argues, is practising apartheid.

What is apartheid ?

Before we get into the system behind the Israeli occupation of the Palestinian territories, it’s worth spelling out exactly what the term apartheid means.

Apartheid in international law refers to a system in which one racial group seeks to maintain dominance over another through systematic oppression and inhumane practices. Racial apartheid became a crime under international law in 1973, in response to South Africa’s regime of enforced racial separation, under which a white minority ruled over and restricted the rights of the Black majority from 1948 until the early 1990s.

“That definition of apartheid is clearly met in the case of Israeli Jewish domination over Palestinians,” Thrall argues. Between the Jordan river and the Mediterranean live roughly 7.5 million Jewish Israelis, who enjoy full rights wherever they live, and 7.5 million Palestinians, who Thrall says, are subjected to varying degrees of discrimination. The difference in who gets to pass freely through the territories, and what treatment they are subject to, is central to his argument.

Thrall says the apartheid charge is now widely accepted across international human rights and legal communities. Human rights organisations B’Tselem and Human Rights Watch made the accusation in 2021, with Amnesty International following suit in 2022.

Successive Israeli governments have strongly rejected that label, arguing it is antisemitic and long warned that it could encourage boycotts against the country or open the door to legal action under international law. Those who reject the apartheid label say that the situation is a temporary, security-driven military occupation arising from a national conflict, not a system of racial domination. They point to the existence of Palestinian citizens within Israel proper with civil rights as evidence.

But a growing number of Israelis disagree, including former head of the Mossad Tamir Pardo. He joins the former speaker of the Israeli parliament Avraham Burg and historian Benny Morris. Even Benjamin Pogrund, a South African anti-apartheid activist who previously defended Israel against the label for The Guardian in 2012 and again in 2015, made a dramatic shift in 2023 when he described the charge as accurate, citing the actions of Netanyahu’s government.

And in July 2024, the International Court of Justice delivered a landmark advisory opinion, declaring Israel’s occupation of Gaza and the West Bank (including East Jerusalem) unlawful. The historic, albeit non-binding, opinion found multiple breaches of international law by Israel, including activities that amounted to apartheid.

The permit system

One of the clearest expressions of what Thrall and other critics calls an apartheid system, is the permit regime governing Palestinian movement. Leaving Gaza, studying elsewhere in the occupied territories, receiving medical care, praying in Jerusalem or working inside Israel all require permits that are rarely granted. It is also embedded in the legal system.

In the West Bank, Thrall adds, Palestinians can discover they are banned from travel without warning, sometimes when they arrive at a border crossing. Hundreds of thousands are thought to be affected by such bans.

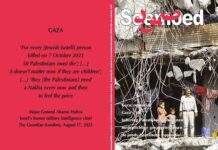

“It’s two entirely different legal systems for Israeli Jews and Palestinians living in the same piece of land,” Thrall says. “You could literally have an Israeli Jew commit the very same crime at the same location on the same date as a Palestinian, and the Israeli Jew will be prosecuted in an Israeli normal civilian court with all the protections of Israeli civil law. The Palestinian would be sent to an Israeli military court where there is a 99% conviction rate.”

The separation is also embedded in physical infrastructure. “There is a segregated road system,” Thrall says. Settlers travel on new, multi-lane highways that cut directly through Palestinian land, while Palestinians are often barred from accessing those same roads. Palestinians are instead diverted on to long, indirect routes that are mostly single-lane, congested, and poorly maintained, often passing under or around settler highways. Israeli authorities refer to these routes as “fabric of life” roads, Thrall explains, while the highways above them are designated for settlers.

It is worth watching this video by the Guardian Middle East correspondent Emma Graham-Harrison on the new road project described by critics as an “apartheid road”.

When I asked Thrall what he says to those citing the 7 October massacre to justify the continued occupation, he stresses the attacks are horrific. He also views the attacks as part of a cycle of violence in the region, linked to the ongoing occupation and restrictions on Palestinians.

The future is now

On the ground in Israel, Thrall sees little reason to believe change will come from within. “When you walk around Tel Aviv or in West Jerusalem, you see the total normalcy, the total ease with which the voters of this country can live with that situation.”

At the same time, the reality for Palestinians is moving in the opposite direction, he adds. Settlement expansion, displacement, and home demolitions continue apace, he says, adding that entire communities are disappearing. Recent reporting by the Guardian’s Graham-Harrison shows the extent of the ethnic cleansing taking place in the West Bank.

“Not only is this not stopping, it’s accelerating. It’s going on at the fastest pace that’s ever happened before,” he says.

Thrall argues that outside pressure is essential. “We in the west have the power to change their perceptions and to change their priorities. And we can do it with very simple things like suspending the EU-Israel Association Agreement and halting arms sales to Israel.

“Imagine a future in which there are two states, or there is one state with equal rights. How will historians describe this period now? It would be a period of apartheid.”

Aamna Mohdin is a community affairs correspondent for The Guardian