Marta Vidal & Meriem Laribi

+972 Magazine / January 30, 2026

After seizing Palestinian land, Jewish settlers are replanting it with vineyards — then exporting their wine as ‘Made in Israel’ to obscure its origins.

A child’s bicycle, an old suitcase, and a single dusty boot lie among the remains of Atiriyah in the South Hebron Hills region of the occupied West Bank — one of a handful of Palestinian communities in the area whose residents fled their homes amid relentless attacks by Jewish settlers in the weeks following October 7, 2023. Next to their scattered belongings, rows of newly planted grape vines now stretch across the depopulated landscape.

“They kept threatening us, every night, every day, every hour,” said 76-year-old Issa Abu al-Qbash, known as Abu Safi, around a month after he was expelled from his home in nearby Khirbet al-Ratheem. “They hit me — five of them — with M16s, right between my eyes, and told me: ‘You will die if you don’t leave. You have five days.’”

Like hundreds of other residents of these communities, Abu Safi fled with his family in fear of their lives, hoping it would be just for a few days. He died several months later, in May 2024, while displaced in the town of As-Samu, longing to return home.

For years, Jewish settlements in the Hebron/Al-Khalil area have been a site of grape cultivation, after successive waves of territorial confiscation. But in recent months, new vineyards have appeared next to the ethnically cleansed communities of Atiriyah, Al-Ratheem, and Zanuta.

As settlers ramp up their attacks with the backing of the state, they are forcing Palestinians off their land at an unprecedented rate and seizing it for the expansion of Jewish settlements. In this context, vine planting for Israel’s wine industry is proving an effective tool of dispossession, providing settlers with economic opportunities while preventing Palestinians from returning to their land.

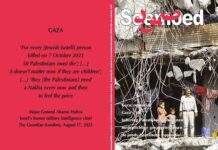

According to data provided by Israel’s Agriculture Ministry, the country has more than 300 wineries producing about 45 million bottles of wine each year. Israel’s Export Institute reports that wine exports have doubled over the last decade. The United States is by far the largest market, accounting for about two-thirds of Israeli wine exports, followed by France (around 10 percent), the United Kingdom (around 5 percent), and Canada (around 3 percent). And wine exports to the United States actually increased after the start of Israel’s genocide in Gaza, from $36 million in 2023 to more than $47 million in 2024.

Although Israel does not distinguish between production within and beyond the Green Line, and wine companies often deliberately mask the origin of their grapes, a report commissioned by the Israel Wine Council and seen by +972 Magazine indicated that the West Bank constitutes one of Israel’s most significant wine-producing regions — alongside the Galilee, the center of the country, the coastal plains, and, in first place, the Golan Heights, occupied from Syria. Indeed, a 2011 report by the NGO Who Profits concluded that “all of the major Israeli wineries use grapes from occupied territory in their wines.”

Seized, razed, replanted

Israel’s Agriculture Ministry estimates that the Golan Heights contain around 1,320 hectares (3,260 acres) of vineyards, though extensive planting over the last three years is not yet reflected in these figures. In the West Bank, determining the full extent of Israeli vineyards is far more challenging, given that official reports are ambiguous as to which wine regions cross the Green Line.

Dror Etkes, an Israeli researcher who has spent more than two decades monitoring settlement activity and founded the watchdog group Kerem Navot, warns that official numbers underestimate the true scale of settler viticulture in the West Bank. “There are a lot of land grabs that are not reported — we can see expansion in the last few years,” Etkes told +972 Magazine as he examined his database, in which he has mapped about 1,300 hectares (3,200 acres) of settler vineyards in the West Bank.

Etkes estimates that there are around 89 hectares (220 acres) of recently planted vineyards in areas from which Palestinian communities have been forcibly displaced in the southernmost part of the West Bank. Several companies are known to grow grapes and produce wine in the Hebron region, including Antipod in Kiryat Arba, which markets wine under the labels Jerusalem Winery, Noah Winery, and Hevron Heights Winery; Drimia Winery in Susya; La Forêt Blanche in Beit Yatir; and Ba’al Hamon, an agricultural company that also cultivates vineyards in the South Hebron Hills.

Some of these companies are also connected to violent settlers. La Forêt Blanche was founded by Menachem Livni, who was convicted of murdering three Palestinian students in Hebron and wounding 33 others in 1983 as a ringleader of the extremist Jewish Underground; he was released after about seven years following presidential clemency and began cultivating grapes near Hebron. Company filings obtained by Kerem Navot also show that Ba’al Hamon lists Shimon Ben Gigi among its shareholders, a security coordinator at the illegal outpost of Havat Maon who has been named in multiple incidents of violence and harassment against Palestinians.

The largest concentrations of settler vineyards, however, are farther north, around the settlements of Gush Etzion near Bethlehem, and Shiloh in the Nablus region — home to wineries such as Shiloh, Gva’ot, Har Bracha, and Tura.

On his laptop, Etkes showed us aerial images documenting the gradual dispossession of Palestinian farmers over decades, as their lands were seized by settlers, razed, and replanted with vines. “The vast majority of the land used by settlers [for vineyards] is privately owned by Palestinians,” he explained.

Ziad Rida and his siblings inherited some 10 hectares (25 acres) of olive groves and farmland in Qusra, a village south of Nablus, on which his family grew wheat, lentils, and chickpeas. “We cultivated the land together,” he told +972 Magazine. But in 2009, settlers took over a hilltop on the family’s land — and soon began erecting barriers to block the family’s access and cultivating grapes.

“We tried to remove the barriers, but they came with army protection,” Rida explained. “They planted vines and kept expanding, taking more land.” After October 7, the area was completely closed off.

The dispossession of Palestinian farmers stretches back decades. Since 1967, Israel has seized more than 200,000 hectares (500,000 acres) of land in the West Bank — over one-third of the territory — depriving Palestinians of their land and livelihoods.

In the nearby village of Qaryut, close to the settlement of Shiloh, Shaher Musa remembers vividly when his village’s land was seized to establish a vineyard in 1996, including plots registered under his grandfather’s name during the Ottoman period. “The entire area was bulldozed, flattened, and planted with vines,” he explained.

Over the past two years, land grabs have accelerated dramatically. According to Qaryut’s village council, residents are now cut off from nearly 90 percent of their land. Settlers also took over the village’s springs, one of which they turned into a swimming pool.

While Palestinian farmers like Musa are deprived of their water sources, settlements that are all illegal under international law — and even outposts that are ostensibly illegal under Israeli law — are quickly connected to water and power grids. East of Shiloh, Israel’s national water company recently installed a large water container in the middle of extensive vineyards on land seized from Palestinians.

Alongside water for irrigation provided by Israel’s state company, settler vintners receive generous subsidies, grants, and tax benefits in both the West Bank and the Golan Heights, which are designated as “national priority areas.” Shiloh Winery alone has received more than NIS 4 million ($1.27 million) in government funding over the last decade, according to data obtained by the organization Peace Now. A 2018 governmental publication details an approved NIS 19 million (over $6 million) investment plan for Shiloh and two other wineries.

Obscuring origins

While Israeli wineries are generally open about cultivating grapes in the Golan Heights, those sourcing grapes from West Bank vineyards often try to obscure their origins through misleading labels and supply-chain mixing — a direct response to increasing efforts worldwide to boycott and outlaw settlement products.

In July 2024, the International Court of Justice outlined obligations for states to “abstain from entering into economic or trade dealings with Israel concerning the Occupied Palestinian Territory” and to “take steps to prevent trade or investment relations that assist in the maintenance” of illegal settlements. For now, however, this ruling does not seem to have had much of an impact.

“Exports to Europe have not been significantly affected by the tensions of recent years,” Mark Gershman, head of the wine sector at Israel’s Export Institute, said in an emailed statement. “While specific markets have been stagnant or in slight decline in recent times, other and new markets are on the rise,” for example in central and eastern Europe.

The European Union, Israel’s largest trade partner, has adopted several policies to distinguish between Israel’s internationally recognised borders and the territories it has occupied since 1967. The first step came in 2004, when the EU began requiring Israeli exporters to provide postal codes indicating the place of production so that settlement goods would not receive preferential treatment under the EU-Israel trade agreement. This approach was bolstered in 2012, when the EU sought to exclude the occupied territories from Israel-EU agreements.

In 2015, the EU issued a notice requiring clear labelling of products made in Jewish settlements. The Court of Justice of the European Union reinforced this regulation in 2019, ruling that member states must ensure distinct labelling for settlement products, which cannot be marketed as “Made in Israel.” Gerard Hogan, the court’s Advocate General, compared the case to the boycott of South African products during apartheid, arguing that some consumers may wish to avoid buying settlement products out of concerns around “political or social policies which that consumer happens to find objectionable or even repugnant.”

There have also been international moves in the opposite direction. In 2020, after visiting Psagot Winery, built on privately owned Palestinian land east of Ramallah, then-U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo announced a new policy requiring products from Jewish settlements to be labelled “Made in Israel” — a policy that was later the subject of the Anti-BDS Labelling Act of 2024 which intended to codify it into U.S. law. As a gesture of gratitude for pro-settlement policies, Psagot Winery created a “Pompeo” label.

For many international law experts, however, labelling measures fall short of the legal response required. “It’s as if you put ‘Made with child labour’ on a product and then explained that it’s up to the consumer to decide whether or not to buy it,” François Dubuisson, a professor of international law at the Université Libre de Bruxelles (ULB), told +972. “It’s basically a kind of token policy meant to save face.”

Given that the settlements are illegal under international law, Dubuisson argues that products produced there should be banned outright. Such a move wouldn’t be unprecedented: Following the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014, the EU moved swiftly to ban imports from Russian-occupied Crimea.

“The position of European and Western countries is not surprising,” said Nazeh Brik, a researcher at Al-Marsad, a human rights organization based in Majdal Shams in the Golan Heights. “The issue of covering up [Israeli] products and their sources is very small compared to [their] support for the extermination of the Palestinian people.”

Brik, who published a report on the settler wine industry in the Golan Heights, added: “Even when the law says products must be labelled, it is not implemented.” Indeed, a 2020 report by the European Middle East Project (EuMEP) found that only 10 percent of wines produced in the occupied West Bank and Golan Heights were sold in the EU with correct labels. And during our investigation, we did not find a single instance of proper labelling among the hundreds of bottles examined in European shops.

Labels on bottles from Jerusalem Winery sold in France as “Made in Israel” list addresses that don’t match their actual production site in the settlement of Kiryat Arba, near Hebron. Company documents from Israel’s corporate registry indicate it may be using the address of a bottling facility and its administrative registration to obscure the true origin of its wines and therefore unfairly benefiting from preferential treatment in EU trade agreements.

In an interview with the French magazine Torah-Box last November, Michel Murciano, the owner of Jerusalem Winery, Hevron Heights Winery, and Noah Winery, acknowledged that “because of the BDS movement, two of our brands do not mention ‘Hebron’ in order to avoid losing certain markets.”

A 2025 report published by Oxfam in collaboration with more than 80 civil society organizations documented how Israeli exporters deliberately evade regulations by mixing settlement products with goods made within Israel’s recognised borders, or by listing fictitious addresses within Israel to obtain preferential trade treatment. Meanwhile, companies that clearly label their products as originating in settlements can receive compensation from Israel’s Finance Ministry for the loss of customs exemption benefits.

After two years of carnage in Gaza, the European Commission proposed to suspend Israel’s preferential access to the EU market, which would result in roughly €227 million in additional customs duties annually. But without majority backing and following the announcement of a ceasefire in Gaza, the proposal never moved forward.

The importance of Israel’s wine industry extends far beyond its economic value. According to a report prepared by the consulting agency Herzog Strategic for the Israel Wine Council and seen by +972 Magazine, the sector makes a “substantial contribution to strengthening settlement and Jewish agricultural heritage,” and plays a key role in developing “rural tourism.”

The report also highlights the role of wine in promoting foreign relations, particularly through Israel’s participation in international wine competitions. Prestigious platforms such as the Decanter World Wine Awards have granted medals to wineries like Shiloh, Gva’ot, and La Forêt Blanche, located in some of the most violent parts of the West Bank. The awards help normalize the illegal settlements and reward businesses that profit from the dispossession of Palestinians.

When contacted for comment, Decanter said it is “currently reviewing its internal policies and procedures relating to wines produced in territories with disputed or sensitive legal status. As this review is ongoing, we are not in a position to respond to the specific questions raised.”

Settler wineries have also built partnerships with clients around the world. On an episode of the podcast “The Kosher Terroir” in May 2025, La Forêt Blanche’s CEO Yaacov Bris mentioned an agreement to supply wine to 18 Club Med hotels in the Alps. The partnership was made discreetly, he explained, to avoid potential boycotts or negative publicity. In response to an inquiry, Club Med denied that any such agreement currently exists; when presented with a menu from Club Med Val d’Isère available online on which La Forêt Blanche appears in the wine list, the spokesperson stated that it is an old menu and that they no longer sell this wine.

Amichai Lourie said his Shiloh Winery “operates in full compliance with Israeli law, transparently and responsibly.” Elyashiv Drori, the co-founder of Gva’ot, denied that his winery was established on occupied land. “The Arabs came into this land as nomads and later as conquerors,” he responded, adding that the land “was promised by God to the Hebrew people.” Tura, Har Bracha, and La Forêt Blanche did not respond to requests for comment.

‘Selling the West Bank as Tuscany’

The colonial roots of Israel’s wine industry go deeper than 1967; they can be traced all the way back to the early days of Zionism. In the late 19th century, Baron Edmond de Rothschild, a French scion of the Rothschild banking family and strong supporter of Zionism, purchased land in Palestine and imported French grapevines, hoping to create economic opportunities for Jewish settlers.

Israeli researchers Ariel Handel and Daniel Monterescu note that this effort to modernize viticulture in the Jewish colonies drew on the idea of wine as an agent of culture and progress. Despite significant investment, the project failed: The French vines were poorly adapted to the local climate and soil, and the wines didn’t gain traction in foreign markets.

“Israel wasn’t known for wine until the beginning of the 1990s, with the establishment of the Golan Heights Winery,” Handel explained. Wine, he said, became a tool to rebrand the Golan “not as an occupied territory, a place of wars, a place of blood, but rather as ‘Europe in Israel.’ It became a place of tourism and good taste.”

Wine played such a prominent role in normalizing the occupation of the Golan Heights that the model is now being reproduced by settlers in the West Bank. “They started to sell the West Bank as Tuscany: wine and cheese, bed and breakfast,” Handel noted.

Here, settler vintners cast themselves as pioneers who are “bringing back winemaking after 2,000 years” and “reviving” biblical wine traditions. The website of Michel Murciano’s Jerusalem Winery, for example, states that the annual grape harvests are taking place “while waiting for the final stage where the Temple of Jerusalem would be rebuilt and where we would be able to bring our wine to the priests.”

Winemaking, Monterescu explained, “has a very profound cultural and religious resonance. So it’s both a means of expansion and land grab, but also has an index of religious rootedness.”

As in much of the Mediterranean, grapevines have grown in Palestine for millenia. Vines are mentioned hundreds of times in the bible, and archaeological digs in the area have found ancient wine presses. Today, settler winemakers seek to link modern viticulture with the biblical texts, placing special emphasis on indigenous grape varieties. “Some names appear in the Jewish texts, and we find them in Palestinian villages with slightly different names,” Monterescu noted.

While wine production declined under Islamic rule due to the religious ban on alcohol for Muslims, it never vanished, with local Christian and Jewish communities continuing to produce wine long before the arrival of Zionist settlers. The Cremisan Valley, between Jerusalem and Bethlehem, is home to the Palestinian-run Cremisan Winery, founded in 1885 by Salesian monks. “Even before Cremisan was established, many Christian families produced wine at home,” winemaker Fadi Batarseh told +972 Magazine in his office, overlooking the region’s ancient terraces.

Grapes remain one of Palestine’s most abundantly grown fruit crops. Although wine grape cultivation declined under Islamic rule, farmers continued to grow table grapes and preserve local varieties. These grapes are consumed fresh and also processed into raisins, molasses, vinegar, and sweets, while the leaves are harvested for use in a variety of local dishes.

Batarseh was part of a team that mapped the indigenous grapes of Palestine. “We did a genetic analysis and found there are 21 different genotypes, four suitable for wine: three whites and one red,” he explained. In 2008, Cremisan began producing wines from these indigenous varieties — Dabouki, Hamdani-Jandali, and Baladi — which went on to receive international awards. Following Cremisan’s success, Israel’s Recanati Winery launched a similar wine in 2014 using grapes bought from a Palestinian farmer near Bethlehem.

According to Handel and Monterescu, there were two Israelis responsible for sourcing indigenous grapes for Recanati: Shivi Drori, a molecular biologist at Ariel University and co-founder of Gva’ot Winery, both of which are located in settlements in the northern West Bank; and his student Yakov Henig, from the Gush Etzion settlement bloc near Bethlehem, who used his connections with Palestinian farmers to locate native grapes.

Interviewed by Handel, Henig also recalled finding “wild grapes” in the ruins of destroyed Palestinian villages. He said it was then that he realized the best tool for finding indigenous varieties for his research project with Drori was a map of the hundreds of Palestinian villages depopulated and destroyed during the Nakba, produced by the anti-Zionist Israeli NGO Zochrot.

Palestinian farmers who kept endemic vines alive became “gatekeepers” of ancient viticultural knowledge, Monterescu explained. But once Israeli winemakers secured access to the grapes, the Palestinian farmer “became redundant — they don’t need him anymore, because they already took the grapes. Now you have dozens of local wineries making Dabouki, Jandali, Hamdani,” and marketing indigenous varieties as “Israel’s ancient biblical grapes.”

And while settlement wines made on stolen land move freely through global markets, Palestinian products face strict inspections, as those cultivating the vines endure escalating attacks from settlers aiming to seize their land and resources.

“We cannot import or export anything freely,” Canaan Khoury, a winemaker from the Palestinian village of Taybeh in the West Bank, told +972. “It costs us more to get the wine from the winery to the port than from the port to Tokyo because of the extra security checks and the restrictions. For every shipment, we have new regulations that the Israelis impose on us.”

The challenges go far beyond shipping. “We’ve endured land confiscations by the army, and we face constant settler attacks,” Khoury said. “They attack vineyards. You will find rows of vines of different ages because every time settlers come, they cut down some of the vines, and we have to replant them. We’re also not allowed to access our own water supply. The Israelis steal our water and sell it to us in limited quantities.” A few weeks after our visit, one of Taybeh Winery’s vineyards was attacked again.

Despite these hardships and the uncertain future, Khoury continues to tend his vineyards, harvest grapes with his family, and produce wine. “We keep producing more and building new facilities,” he said with a wry smile. “We joke that we’re making these for the settlers to come and take from us.”

This investigation was supported by Investigative Journalism for Europe (IJ4EU) in partnership with Le Monde Diplomatique and IrpiMedia. Omri Eran-Vardi and AIN Collective contributed reporting.

Marta Vidal is an independent journalist focusing on social and environmental justice across the Mediterranean

Meriem Laribi is an independent journalist; she is the author of two books: Ci-gît l’humanité, Gaza le génocide et les médias (Critiques 2025), and Palestine, le droit à l’existence (Critiques 2026)