The gavel and the gun

Darryl Li

Jewish Currents / June 17, 2025 [Summer 2025 issue]

Palestinian history shows that armed struggle campaigns often catalyse gains in international lawmaking.

Since Hamas launched “Operation al-Aqsa Flood” on October 7th, 2023, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in the Hague, the highest court in the United Nations (UN) system, has devoted over a third of its hearings to Palestine — more than it has to any other issue. In January 2024, the court green-lit South Africa’s genocide suit against Israel, a striking development given how often Israel has couched its own legitimacy, and by extension its annihilatory violence, in relation to the Nazis’ genocide of Jews. In July, in perhaps the most significant legal defeat Israel has ever faced, the ICJ went further and ordered that the occupation of East Jerusalem, the West Bank, and the Gaza Strip end “as rapidly as possible.” Though various UN bodies, including the ICJ, have criticized the lawlessness of Israeli occupation policies for decades, the July opinion was the first ever finding of apartheid from an international court, and the first to order Israel’s total withdrawal from the parts of Palestine it conquered in 1967 without requiring a prior negotiated settlement. In November, the rapid accumulation of Palestinian legal advances continued as the International Criminal Court (ICC), a separate body also based in the Hague, issued arrest warrants for Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and former Defense Minister Yoav Gallant on charges of war crimes and crimes against humanity—breaking its previous pattern of indicting only non-Western leaders or functionaries. The legal movement persisted into December, with the ICJ opening a separate case challenging Israel’s attempts to effectively shut down the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA), which provides humanitarian aid to Palestinian refugees.

It’s not unreasonable to assume that such unprecedented moves in international law, as belated and inadequate as they may be, simply reflect the unprecedented horror of Israel’s genocidal war in the Gaza Strip. There is some truth to this, especially when the scale, speed, and ferocity of Israel’s destruction of Gaza has blown through virtually every record in the history of modern warfare. But Palestinian history is littered with outrages unprecedented in their own time that either went unanswered or failed to generate commensurate responses. In 1982, for instance, the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) passed just one resolution calling the Sabra and Shatila massacre, in which Phalangist Israeli proxies in Lebanon murdered thousands of Palestinian refugees, an act of genocide, but no international legal body ever took the matter further. Instead, in the past as now, what appears to propel international law to respond on Palestine is pressure from anti-colonial struggles. This explains why the historical high point of Palestinian legal efforts — pursued not just in the courts but also in quasi-legislative international bodies like the UNGA — took place in the 1970s, which was not necessarily a moment of record-breaking body counts. At that time, the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) managed to mobilize the Palestinian and Arab masses and drew the sympathies of a decolonizing Global South majority amid a wave of successful independence movements that redrew the world map and packed the UN with new states. The PLO’s movement eventually led to a remarkable series of legal wins for the Palestinian cause, including the international recognition of the Palestinian people’s right to self-determination and of the PLO as their representative, as well as the expansion of the rules of war to legitimize anti-colonial warfare.

In her book Justice for Some: Law and the Question of Palestine, the legal scholar Noura Erakat offers a helpful metaphor for understanding what drives international law. Likening the law to the “sail of a boat” — a structure that guarantees only motion, while the “wind” of political mobilization “determines direction” — Erakat writes: “The law is not loyal to any outcome or player, despite its bias towards the most powerful states. The only promise it makes is to change and serve the interests of the most effective actors.” This analysis illuminates why international law evolved in response to Palestinian pressures in the ’70s, and why it has become a site of renewed energy in the Palestinian struggle after October 2023, as it has caught the rising anti-war and anti-colonial winds of global mass protests, direct actions shutting down infrastructure and disrupting arms manufacturers, encampments at colleges and universities, and endless small-scale confrontations in governmental, corporate, and nonprofit workplaces.

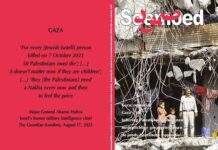

In examining these two moments in tandem, it is impossible to ignore that they are connected not only by the “wind” of popular mobilization but also by another factor: the centrality of armed struggle to the Palestinian politics of the day. Whether the PLO’s struggle out of Palestinian refugee camps in the ’70s or Hamas’s urban guerilla campaign in the Gaza Strip today, armed struggle — not mere violence, but rather organized force grounded in mass movements — has historically been a bloodstained lever moving the question of Palestine onto the international legal agenda. The reasons for this are straightforward enough. Compared to other oppressed peoples who may seek independence or autonomy — whether colonized populations in formal European colonies like India and Algeria, or minorities in non-Western states such as the Kurds in Turkey, and the Tibetans in China — the Palestinians are “dealing with a colonist state that had no project of incorporating them, even as oppressed subjects,” the historian Abdel Razzaq Takriti told me. Faced with such an eliminationist adversary, Palestinians cannot vote, protest, or strike their way out of dispossession. They may not be able to fight their way out either, but at the very least their struggle has demonstrated the capacity to threaten regional and international stability and force states to respond, including and especially through international forums. “Had Palestinians not developed their own independent military capacity,” Takriti said, “their national liberation cause would have been erased a long time ago, and their inalienable rights would not have achieved any international recognition.”

In the ’70s, Palestinians commanded attention by launching an armed and mass movement that was internationalized by nature due to their exile across Arab states. That struggle quickly catapulted to global attention after it provoked Israeli attacks on multiple host countries, destabilizing the entire region. Diplomats around the world read the disruption as a call for legal and political action, with a representative from Spain telling a 1970 UNGA plenary meeting that “the conflict in the Middle East is, in the opinion of the Spanish delegation, the most critical of all the conflicts afflicting mankind at the present time,” a widely expressed sentiment at that gathering. Unless the UN acted to stop the unfolding chaos, the Spanish diplomat added, “the present potential war will inevitably lead to another confrontation, with the obvious risk that it could become a world conflagration.” Now, over 50 years later, Operation al-Aqsa Flood is operating similarly, unleashing not merely a global current of public pressure, but also the threat of regional war through the interlinked fronts of Lebanon, Iran, Iraq, and Yemen. It has shaken up the international status quo and emboldened emerging powers like South Africa to pursue more aggressive action in international forums. Even establishment courtiers like New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman, who calls Hamas “a sick organization that has done enormous damage to the Palestinian cause,” cannot fail to take note of the pressures the group has generated, arguing in a recent op-ed that the current situation of “permanent insurgency” in Gaza — which he calls “Vietnam on the Mediterranean” — must be addressed politically, lest it “inevitably threaten the stability of Jordan and the stability of Egypt” and undo the very “pillars of America’s Middle East alliance structure.”

To suggest that the “good” of international law and the “bad” of violence cannot be readily disentangled may seem counterintuitive or even scandalous, especially when anti-colonial violence transgresses international legal prohibitions against targeting civilians and taking hostages. But such violations hardly set anti-colonial guerrillas apart from the regimes they oppose; after all, what is at stake is legitimacy on the world stage, the right to participate in what the political scientist Stephen Krasner famously called the “organized hypocrisy” of the international legal order. And while anti-colonial violence may alienate potential allies and supporters in the West, non-Western states that see themselves as heirs or allies to such struggles still hold significant sway in the UN and other international institutions (what Zionists deride as the “automatic majority” that routinely votes in condemnation of Israel). This support is so significant that, along with the threat of Russian and Chinese vetoes at the Security Council, it has contributed to repeated blockage of Western efforts to add Hamas and other Palestinian factions to UN terrorism lists; as a result, armed operations carried out by such groups retain some international legitimacy to this day.

Of course, then as now, advances for Palestine in international fora could not stop Israeli aggression. The genocide continues, and no one expects to see Israeli war criminals in the dock any time soon. Indeed, for decades, efforts at international lawmaking on Palestine have been listlessly caught in a space between never enough and better than nothing, part of what the anthropologist Lori Allen has called a “history of false hope.” As a South African justice lamented last year, when the ICJ belatedly ordered a ceasefire in Rafah that Israel promptly ignored, “the Court is only a court!” At its worst, the law has been a weapon against the weak, as we saw when the ICC prosecutor sought arrest warrants for three Hamas leaders alongside Netanyahu and Gallant, on arguably more serious charges. In the face of Israel’s utterly asymmetric death-dealing in Gaza, the prosecutor’s attempt at “balance” works to delegitimize Palestinian armed struggle in legal terms, even as Israel attempts to stamp it out in practice by simply killing Hamas leaders before they can ever be arrested.

And yet, despite their inability to stem colonial violence, international legal wins can present movements with new opportunities to exert pressure. In the ’70s, the PLO’s legal strategy powered its larger fight, turning global solidarity with Palestine into material benefits — like the ability of PLO leaders to travel (including on diplomatic passports), raise funds, and obtain weapons more easily. Today, as the threat of regional war, the activism of some Global South governments, and the popular pressure in the streets of the Global North spur international lawmaking on Palestine, we are again seeing legal gains become useful as openings for further struggle. Already, 14 states — including Spain, Ireland, and Belgium — have signalled their intention to formally intervene in support of South Africa’s petition alleging genocide in Gaza, and others may follow. The circle of confrontation has also broadened to encompass Israel’s close allies, with Germany facing its own genocide case from Nicaragua over its arms transfers to Israel and its attempts to defund UNRWA. Germany even quietly slowed arms transfers to Israel for a short time, and has now publicly said it will reassess the shipments due to legal concerns. In the best cases, activity in the courts has fed back into movements: South Africa’s largest federation of trade unions, for instance, has used the ICJ case as an opportunity to denounce coal shipments to Israel, asking why the government maintains diplomatic and trade relations with a genocidal state. Certainly, there are important differences from the ’70s conjuncture; the decolonial momentum of that era is long gone, and the divisions in Palestinian politics leave the national movement without a clear representative. For all their limitations, however, recent developments clarify that the path ahead lies not in closing the gap between law’s promise and its enforcement, but in turning that gap into a means of regenerating and channelling popular energies. The history of anti-colonial lawmaking suggests that the law’s true utility lies not in its ability to directly constrain the colonizer, but in the tools it offers the colonized to remake the terrain of political struggle.

At first, Palestinians experienced international law primarily as a tool of dispossession. A League of Nations mandate enshrined the Balfour Declaration’s support for a “Jewish national home” in Palestine in international law, and a 1947 UNGA resolution called for the partitioning of the country, which set the stage for the mass expulsions of the Nakba, when Zionist forces exiled more than 700,000 Palestinians beyond the boundaries of what became Israel. Most Nakba refugees ended up in neighbouring Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria, an exile that was not only geographical but also legal. In an emergent order of newly independent nation-states, Palestinians no longer had a country to return to nor any claims to citizenship anywhere, an outsider status that the Palestinian lawyer Ardi Imseis has called “international legal subalternity.” With Palestinians largely lacking any representation in the international system, by 1952 the question of Palestine had disappeared from the agenda of the United Nations, a situation that worsened after the completion of the Zionist conquest of historic Palestine in 1967—when the UN Security Council produced a framework that treated the Palestinian question as a humanitarian “refugee problem” rather than a political one.

If the international legal order was inherently enemy territory, the anti-colonial movements of the mid-20th century nevertheless significantly reshaped its contours. In the decades after the Nakba, national liberation struggles had won independence from colonial rule in most of Africa and Asia. Western governments were a minority in the UNGA, which made it a key venue for Third World states to create a counterbalance to the Security Council, and engage in what the political theorist Adom Getachew has called “anti-colonial worldmaking.” Suddenly, the conservatism of formal international law principles like equality and non-interference between state sovereigns seemed like a useful way to protect the gains of successful anti-colonial movements, and to power the struggles of ongoing ones.

Entering this favourable context, Palestinians transformed their refugee camps in Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria into bases of an armed liberation struggle, one often referred to as “the Palestinian revolution.” The Palestinian guerrilla operations that followed kept the region in a permanent state of low-level war, as Israel’s attempts to eliminate Palestinian resistance invariably entailed attacks on Arab host states. US-backed regimes, such as the one in Jordan, soon came to see Palestinian militancy as a threat to their stability. Indeed, confrontations between Israel and the PLO helped catalyse civil war in Jordan during the “Black September” of 1970, when Jordan used a multi-plane hijacking by Palestinian guerrillas as a pretext to forcibly evict the PLO from the country. Conflict also broke out in Lebanon beginning in 1975, which included fighting between Israeli-backed proxies and the PLO and their allies. The most destabilizing moment came in 1973, during what is known in Israel as the Yom Kippur War — when Egyptian and Syrian militaries launched a surprise attack on Israel that was only contained thanks to an emergency US airlift of weapons. The PLO was involved in the conflict, with its guerillas and leaders participating in the war’s planning and execution. By triggering violence across borders, the Palestinian struggle created outsized pressure at the international level, becoming impossible for the international system to ignore. And the more the US had to intervene to prop up Zionism, the more it risked antagonizing regional players—as seen most dramatically when US support for Israel in 1973 provoked the Saudis into declaring an oil embargo that drove up fuel prices and catalysed an inflationary spiral for US consumers. This ability to upend regional and global politics proved crucial not only for the PLO’s leverage, but also its legitimacy: A month after the October 1973 war, for instance, the Arab League recognized the body as the sole representative of the Palestinian people. After decades of being spoken for by Arab states, the PLO’s commitment to armed resistance had solidified its status as the leader of the national movement, a representative that governments and international bodies had to deal with.

In the early ’70s, PLO leader Yasser Arafat launched a diplomatic offensive in this newly receptive moment. The campaign that followed secured a rapid succession of legal wins in a matter of a few years. First came the widespread recognition of the Palestinian people as a nation with the right to self-determination, culminating in a 1970 resolution at the UNGA. Soon afterward, the PLO achieved recognition as the representative of the Palestinian people, and on that basis became the first national liberation movement to be granted observer status at the UN; this gave the Palestinians, unusually among stateless peoples, an institutionalized voice that could speak in their name on the world stage. In 1974, Arafat was invited to address the UNGA. In a moment that represented a major diplomatic triumph, the PLO leader—whose speech was interrupted multiple times by applause from the assembled dignitaries—famously announced that he came “bearing an olive branch and a freedom fighter’s gun,” making explicit the understanding that he would not be addressing the UNGA if not for armed struggle.

In the years that followed, the PLO continued to make significant gains on the international legal front. In 1975, the UNGA passed a historic resolution declaring Zionism to be a form of racism. Until that point, the UN had generally affirmed Palestinians’ rights without naming their oppressors; the Zionism resolution concretized in law an explicitly anti-colonial analysis of the struggle against Israel and helped pave the way for future statements describing the Palestinians as a people facing colonialism. Later UNGA resolutions explicitly “reaffirm[ed] the legitimacy” of anti-colonial movements, including that of the Palestinians, to proceed “by all available means, including armed struggle.” All of this was critical in preventing Israel from fully normalizing its conquests in international fora. It also enabled the growth of a robust Palestinian diplomatic apparatus with offices around the world and facilitated the flow of aid from sympathetic states, from Chinese guns to Yugoslav medical aid to Soviet university scholarships.

Perhaps the most striking development of this era came from multilateral negotiations in Geneva to update the rules of warfare. The PLO and other anti-colonial movements were allowed to participate in the gathering, which resulted in the 1977 First Additional Protocol to the Geneva Conventions; this codified many of the rules of warfare now considered axiomatic, including the prohibitions on targeting civilians and on indiscriminate attacks. What interested the PLO and other national liberation movements was not so much the rules themselves (which they, like most states, had no trouble disregarding when convenient) but the extension of the privileges ordinarily reserved for state armies to movements “fighting against colonial domination and alien occupation and against racist regimes in the exercise of their right of self-determination.” Soundly outvoted, Israel and the US refused to support the protocol, which gained near-universal acceptance nonetheless. (The US came crawling back a decade later by bizarrely opting in à la carte, issuing a list of articles in the protocol that it believed were binding.)

Gradually, however, the PLO’s diplomatic and legal strategy displaced mass politics, including armed struggle, and took the wind out of the movement’s sails for decades to come. Even as it won novel acknowledgment of the legitimacy of anti-colonial violence, the PLO leadership increasingly judged that further legal and diplomatic gains would require moving away from a military strategy. The organization’s leadership had already begun moving in this direction as early as 1974. That year, Arafat watched Egypt enter into US-brokered negotiations with Israel. Sensing the creation of a pathway to Arab–Israeli normalization — which would remove the most powerful Arab state from the confrontation with Zionism — he responded with a diplomatic overture in the form of a “ten-point program,” which maintained the PLO’s stated goal of replacing Israel with a democratic secular state, but proposed doing so in a phased approach. The proposal sparked an uproar across the PLO, and especially from the organization’s second-largest faction, the Marxist-Leninist Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), which saw the phased approach as a tacit acceptance of accommodation with Zionism through partition and a signal that Arafat would abandon armed struggle without achieving liberation. After Arafat’s UN speech, a PFLP newsletter reminded readers that “armed struggle was the chief reason for this diplomatic success. Hence we postulate that it is this same vehicle which must not be abandoned in order to advance and develop the Palestinian resistance movement.” The PFLP’s warning proved prescient. Within a decade, normalization of ties with Egypt allowed Israel to invade Lebanon with far less fear of triggering a broader Arab–Israeli war, ultimately removing the PLO’s main source of military pressure on Israel and derailing the revolution of the refugee camps.

Even as it won acknowledgment of the legitimacy of anti-colonial violence, the PLO leadership judged that further legal and diplomatic gains would require moving away from a military strategy.

As the national movement fractured through the ’80s, the PLO embarked upon a legal strategy that, even when it coincided with popular mobilization, was not able to build on their momentum. In 1987, the First Intifada broke out in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, featuring protracted mass mobilizations and strikes, and marking a shift in the center of gravity of Palestinian politics from the refugee camps in Arab states to the parts of Palestine conquered in 1967. At first, this was remarkably successful in pressuring the Israeli polity due to Israel’s dependence on Palestinian workers and consumers. The PLO leadership in exile used the leverage of the Intifada to lean further into its bid for international legal recognition, declaring the establishment of a “State of Palestine” with unspecified borders in 1988. (The declaration’s favourable mention of the 1947 UN partition resolution signalled the PLO’s potential willingness to compromise with Israel.) Yet Israel managed to adapt to the pressures of the First Intifada, gradually reducing its dependence on Palestinian labour. Meanwhile, having lost its leverage on the battlefield, the PLO’s desperation to get Israel to the negotiating table generated only concessions. In December 1991, the PLO acceded to repealing the UN resolution designating Zionism as a form of racism as a quid pro quo for Israeli participation in diplomatic talks in Madrid. But the sit-downs proved unsuccessful for Palestinians, while Israel reaped rewards from its tepid engagement, which allowed it to finally establish full diplomatic relations with both China and India, the two largest countries in the world that were also longtime allies of the PLO.

The Oslo Accords that capped these years of negotiations only solidified the PLO’s shift away from anti-colonial resistance. The agreement established an interim body, the Palestinian National Authority (more commonly known merely as the Palestinian Authority, or PA, mirroring Israel’s dismissal of its aspirations to statehood), which accepted a role as Israel’s security subcontractor in the 1967 territories. This made Palestinian leaders responsible for suppressing revolutionary activity in the future, all but guaranteeing that they would be delegitimized in the eyes of the people they purported to represent. As a result, by the time the Second Intifada rolled around — favouring violence where the First had favoured mass mobilization — the PA’s capitulations at Oslo ensured that the movement would remain confined to individualized militant actions (especially martyrdom operations, or “suicide bombings”) rather than an organized strategy of armed resistance led by a representative body, as in the ’70s.

After the First Intifada, and amid the PA’s detachment from any effective legal strategy, a new generation of Palestinian civil society organizations emerged as significant players in Palestinian international lawyering. Groups such as al-Haq, the Palestinian Center for Human Rights (where I worked in the early 2000s), al Mezan Center for Human Rights, and Addameer sought to activate the growing post–Cold War landscape of human rights and humanitarian law mechanisms to hold Israel to account for its treatment of the Palestinians living under its rule. They supplied testimony to various UN bodies about Israeli violations of international law, lobbied governments (especially European ones) to pressure Israel, and helped bring legal cases in national courts against Israeli war criminals. The high point of this era of international law work came in 2004, when the PLO’s UN alliances and the NGOs’ legal savvy came together to produce a resounding legal victory at the ICJ, in the form of an advisory opinion declaring the separation barrier that Israel was building in the West Bank to be illegal, and forcing Israel to make modest adjustments to the barrier’s route. The opinion authoritatively confirmed positions widely held in the international community, namely that Israel’s conduct in the West Bank and Gaza Strip was indeed governed by the law of occupation (a position Israel had long resisted, even as it relied on occupation law itself when convenient), and that the Jewish settlements in those territories contravened international law. In the end, however, the ruling constituted a narrow, technical win, rather than a political one: In objecting only to the path of the wall rather than its existence, the ICJ reified the idea that the barrier might be “necessary” for Israel’s presumably legitimate “security objectives.” And while the opinion did help spur activism in the form of the Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions (BDS) movement, which began as a call for its enforcement, the largely external-facing solidarity movement did not feed back into mobilization among Palestinians. Ultimately, the legal strategy of Palestinian civil society groups could not overcome the absence of a national struggle.

In the decade since, the Palestinian leadership has failed to provide a suitable vehicle for national liberation, instead doubling down on a strategy of diplomatic gimmickry. In 2011, the PA launched a desperate campaign for full membership in the UN. It even set up a giant, UN-blue chair in the center of Ramallah to communicate the urgency of filling a Palestinian seat in the international body—a move that became a widely derided symbol of the leadership’s broader approach. Needless to say, such empty publicity stunts did not go far: Facing the threat of a US veto, the PA instead accepted an upgrade from observer to “non-member observer state”; the addition of the word “state” allowed Palestine to join treaties and some UN agencies, including the ICC, but it remained unable to vote. After October 7th, the limits of this strategy have become clearer than ever. In April 2024, the PA lost another bid for full Palestinian membership in the UN after an entirely predictable US veto, suggesting that even sustained global mobilization over the genocide in the Gaza Strip could not elicit new ideas from the Palestinian old guard, or arrest the decline of its relevance.

Today, the entity most explicitly filling the resulting void is Hamas. Since its emergence during the First Intifada, the group has slowly gone from a spoiler to a vanguard in Palestinian politics. In 2011, Hamas secured the release of over 1,000 captives in exchange for one Israeli soldier it had captured. Most significantly, those freed hailed from multiple Palestinian factions, thus demonstrating Hamas’s ability to bring leverage from the battlefield to the negotiating table on behalf of all Palestinians. During the Great March of Return—a sustained set of mass protests at the fence encircling the Gaza Strip in 2018 and 2019—Hamas showed a willingness to support mass mobilizations led by other formations. In 2021, the group responded to settler dispossession of Palestinians in Jerusalem by firing rockets from Gaza; these actions and the resulting Israeli onslaught on Gaza sparked a “Unity Intifada” that included a general strike involving Palestinians on both sides of the Green Line.

Even if international law currently seems to offer a weapon to the Palestinian cause, the ability of a clearly defined Palestinian subject to wield that weapon has never been more uncertain.

Through it all, Hamas did not necessarily develop a political vision that appealed to a majority of Palestinians or address grievances about the shortcomings of its own repressive governance in the Gaza Strip. Instead, the group managed to solidify its position in Palestinian politics by underscoring its commitment to an ideal that transcends party and faction altogether: resistance. Opinion polls of Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza Strip from late 2023 show significantly higher levels of support for Operation al-Aqsa Flood than for Hamas itself, recognizing the former’s importance in putting the question of Palestine back on the world agenda. More tellingly, polls from May show that even many Palestinians who believe the October 7th attack was a strategic error given the severity of the Israeli response remain resolutely opposed to any unilateral disarmament by Hamas—with 85% of respondents in the West Bank and 64% in Gaza answering “no” when asked whether they would support such disarmament in order to stop the war on Gaza. This confirms what for some observers is an uncomfortable truth: that Hamas has become the central actor in the Palestinian struggle.

Theoretically, Hamas’s militancy could generate legal and diplomatic momentum for the Palestinian cause. The group’s recent statements—invoking international law when decrying Israel’s actions, welcoming international court decisions, and thanking those engaged in legal efforts in support of the Palestinian cause around the world—reflect its aspirations to wield this dual strategy. And Hamas has long had an active diplomatic presence, including ties with various Arab states, Russia, China, and, most recently, direct negotiations with the United States. At the same time, there are seemingly insurmountable obstacles to the reemergence of a renewed national liberation movement with Hamas at the helm. The group currently faces a dilemma wherein its actions have helped cement the PLO’s irrelevance, even as international fora still recognize the PLO as the legitimate representative of the Palestinian people—a hard-won asset that Hamas itself recognizes as crucial. Nor can Hamas simply join the PLO; Fatah, the faction that has long dominated the body, has insisted on keeping Hamas out for fear of giving up its own power. Fatah maintains that Hamas can only join if it accepts the Oslo agreements — a thin pretext, given that the PLO’s second-largest faction, the PFLP, has always rejected Oslo, and that Hamas has said repeatedly that it would voluntarily disarm in exchange for a Palestinian state along ’67 borders. This marks a stark contrast from the ’70s moment: Whereas then Palestinians broadly understood the PLO as their representative on the world stage (even as various factions squabbled and competed under its umbrella), today’s Palestinian national struggle is more fractured. Hamas carries the mantle of armed struggle, while an increasingly reviled PA has largely ceded international lawyering to states like South Africa and to the NGOs. None of these actors possesses the broad legitimacy to lead a national liberation movement that could bring together the Palestinian people and their global supporters.

In other words, even if international law currently seems to offer a weapon to the Palestinian cause, the ability of a clearly defined Palestinian subject to wield that weapon has never been more uncertain. But what is clear is this: The question of whether legal achievements become part of the arsenal of struggle or an alibi for inaction will ultimately be answered not in the courtroom, but on the terrain of mass politics—on the streets and, especially, the battlefield.

Darryl Li is an anthropologist and lawyer teaching at the University of Chicago