TNA Staff

The New Arab / February 6, 2026

A shelved report on Palestinian refugees has triggered resignations and rare internal backlash at Human Rights Watch.

The resignation of two researchers from Human Rights Watch has exposed a rare and deep internal rupture within one of the world’s most prominent rights organisations, centred on a shelved report examining Israel’s denial of Palestinian refugees’ right of return.

At the heart of the dispute is a report that had already passed HRW’s internal review process before being halted days before its scheduled publication.

The decision prompted the resignation of Omar Shakir, the organisation’s Israel-Palestine director, as well as assistant researcher Milena Ansari, and sparked internal backlash from staff.

In an interview with The New Arab, Shakir said the report was stopped not because of legal or factual flaws, but because of concerns about political fallout.

“The publication was halted, but it hasn’t been [permanently shelved],” Shakir said. He explained that after the resignations and significant staff uproar, including all-staff meetings and internal letters, HRW leadership said that once an independent review was completed, the report would be taken “back to the drawing board”.

He said HRW’s leadership had proposed reopening discussions around “the methodology, the advocacy and the strategy”, a move he said was deeply frustrating given the report’s status.

“This was a finalised report that was vetted,” he said, adding that even if concerns existed, they could have been addressed through further reviews.

“So while the report is not officially killed,” Shakir said, “I tendered my resignation when I felt that all doors to releasing the report in a principled way, on a timeline that addresses the scale of the urgent crisis, were effectively closed.”

Halted at the final stage

The report was the product of around a year of work and focused on the impact of Israel’s denial of the right of return on Palestinian refugees displaced in 1948 and 1967, as well as those displaced again more recently in Gaza and the West Bank.

According to Shakir, the research was based on dozens of interviews conducted across the region and visits to refugee camps. He said it examined how the denial of return intersects with the emptying of refugee camps in the West Bank, the erasure of camps in Gaza, attacks on UNRWA, and renewed mass displacement.

The report went through the organisation’s normal vetting process and was signed off by every relevant department, including legal and programme teams. By early December, it had been translated, uploaded to the website backend and was ready for publication, with a press release and Q&A finalised. Its publication date was set for 4 December.

Instead, the report was halted just before being sent out to journalists under embargo.

Leadership transition and late intervention

The timing of the decision appeared closely tied to a change in leadership at HRW, Shakir said, with the report halted as Philippe Bolopion assumed the role of executive director.

The intervention came months after a separate, abrupt leadership upheaval at HRW, when the organisation’s board announced the sudden departure of executive director Tirana Hassan in February, a move that staff and board members said came as a shock and was poorly explained.

Hassan, who had been appointed in 2023, said at the time that she was “saddened and surprised” by the board’s decision to end her tenure, while many had warned the opaque process risked undermining trust in the organisation’s governance

“We had a new executive director whose first official day was December 1,” he said. “This report had already been approved through the review process. The reviewers are the same regardless of who the executive director is, and it was scheduled for release.”

While the report had been delayed earlier in the year to address internal feedback, Shakir said the December publication date was finalised. “[The report] was completed and translated, and we were briefing partners because everything was done,” he said.

He said concerns were raised during a briefing with the incoming executive director by several senior colleagues, some of whom had already signed off on the report.

Several days later, the NGO’s new executive director decided to shelve the report.

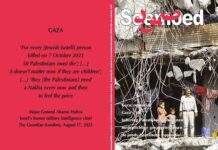

“In my view, that discomfort was not rooted in law or facts,” Shakir said. He argued that the concerns instead related to “being seen as challenging the Jewishness of the Israeli state”, which he described as a political preference that appeared to take precedence over calls to protect fundamental rights.

The New Arab has reached out to Bolopion for comments.

‘Not about the law or the facts’

In response to queries from The New Arab, Human Rights Watch said the report had raised “complex and consequential issues” and that aspects of the research and the factual basis for its legal conclusions allegedly needed to be strengthened “to meet the organisation’s standards”.

Shakir rejected that explanation, saying he and the research team never received a written legal justification for the decision.

“We’ve still, to this day, gotten no explanation in writing beyond concerns of senior staff,” he said. “My months-long engagement with the organisation made clear that this had nothing to do with the law or the facts.”

Discussions behind closed doors pointed instead to fears of backlash, he said.

“Many things were said behind closed doors, but most certainly this was the crucial driving factor,” he said. “The report would essentially threaten the Jewishness of the state of Israel, which would lead to backlash, whether from donors or others.”

Repeated efforts to find a path to publication were blocked in a non-transparent manner, Shakir claimed, with only one meeting held with the report team and key decisions taken behind closed doors.

Internal fallout

Shakir resigned after almost a decade at Human Rights Watch, saying he had lost faith in the organisation’s leadership.

“I resigned because I felt like I had lost faith in our new leadership’s commitment to the core way that we do our work,” he said.

The decision triggered internal dissent, with more than 200 staff members signing a letter warning that shelving the report risked undermining confidence in the organisation’s review process and independence.

Human Rights Watch did not directly address questions from The New Arab regarding whether concerns about political backlash, donor reaction, or pressure from board members played any role in the decision.

In its statement, HRW said the report’s publication was paused pending further analysis and research, adding that the process remains ongoing.

When asked about a timeline, the organisation did not provide any indication of when the review would be completed or when a final decision on publication might be made.

Palestinian refugees and the right of return

More than 700,000 Palestinians were forcibly displaced during the creation of Israel in 1948, known as the Nakba, with further displacement following the 1967 war.

Today, more than five million Palestinian refugees are registered with the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA), living across the occupied Palestinian territories and neighbouring countries.

Israel has long rejected the right of return for Palestinian refugees, arguing that it would alter the country’s demographic balance, while Palestinians and international legal scholars say the right is enshrined in international law, including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Why the right of return proved decisive

Shakir said the episode highlighted the sensitivity surrounding the Palestinian right of return, even within major human rights institutions.

“Look, when you cover Israel-Palestine in a mainstream organisation like Human Rights Watch, you deal with relentless attacks, with unmatched scrutiny, with all sorts of different kinds of pressures,” he said.

He noted that the report had sought to draw lessons from history at a moment of renewed displacement.

“This was coming in the context of the unprecedented ethnic cleansing in Gaza and the West Bank, and the fact that many refugees were again being displaced,” he said.

For Shakir, the refusal to publish the report reflects a lack of will to apply the law consistently when it came to refugees and raised fundamental questions about how far Human Rights Watch was prepared to go when its findings risked political controversy.

Shakir said the damage caused by the decision has already had lasting consequences, both for the organisation and for Palestinian refugees whose stories, he said, remain untold.