Agnese Boffano

The New Arab / January 30, 2026

With governments retreating, global Palestine solidarity has emerged as the main arena of pressure. We speak to GAFP’s Dr Anas Altikriti about unity and power.

London – Donald Trump’s renewed push for a Middle East “Board of Peace” at the World Economic Forum is being framed by its supporters as an attempt to stabilise a region in crisis.

But to critics, it represents something else entirely: a return to top-down diplomacy that sidelines Palestinians, rewards power, and repackages coercion as peace-making.

While political leaders across the world engage in grand initiatives and closed-door bargaining, one force has reshaped the conversation on Palestine more than any government since October 2023: the global solidarity movement.

From mass protests and campus organising to boycotts and union mobilisation, civil activism has challenged the elite-driven narrative and pushed Palestine to the forefront of public life — even as official policy in many capitals remains stubbornly unchanged.

For many public organisers, the shift has been unmistakable: as governments retreat from meaningful action on Palestine, the pressure has shifted to civil society.

But solidarity is not a single movement — it is a patchwork of coalitions, campaigns, and communities that often disagree on tactics, language, and priorities. This fragmentation, activists warn, risks turning global mobilisation into noise rather than power.

It is in this context that the Global Alliance for Palestine (GAFP) has emerged, positioning itself as an umbrella coalition designed to unify grassroots efforts internationally — and translate momentum into sustained influence.

The receding role of governments

In an interview with The New Arab, political strategist and Secretary-General of the GAFP, Dr Anas Altikriti, spoke about the declining role of governments in leading on political issues.

“When you have the Trump way of thinking, or dictating world order by a committee of the wealthy and powerful and those who really have no inkling of how ordinary human beings are suffering, it may seem like a post-apocalyptic scenario, but it is what we’re seeing happen now,” Dr Altikriti tells The New Arab.

Altikriti watched the events unfold in Switzerland and said he witnessed the “true erosion of what we used to call the international community and international order.”

“There is now an awareness that, unfortunately, governments do not want the best for the Palestinian people”

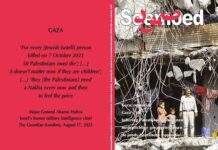

Trump’s board plans to oversee the future governance of a largely devastated Gaza, backed by a $1 billion fund. Meanwhile, Jared Kushner’s $30 billion “New Gaza” plan contained multiple Arabic spelling errors, indicating that no Palestinian reviewers were involved.

“There is now an awareness that, unfortunately, governments do not want the best for the Palestinian people,” Altikriti continues. “They want what makes Palestinians less of a headache, and sometimes that will be shown in positive gestures, and sometimes not.”

Take the UK government as an example. Prime Minister Keir Starmer’s stance on Gaza is largely seen within the pro-Palestine movement as being “morally evasive” — a politics of restraint and reassurance at a time when the scale of Palestinian suffering demanded clarity and accountability.

The opening of a Palestinian embassy in London in January 2026 was largely hailed as a “historic moment”, but in practice, “it makes not a jot of a difference for someone in Gaza,” Altikriti argues.

“What it does do is that it makes Western countries wash their hands and say, well, we’ve done what we could, what more do you want?” he adds.

Solidarity as the central battlefield

With governments increasingly unwilling to lead on Palestine, organisers argue that solidarity has become the primary mechanism through which public outrage seeks political consequences.

Altikriti speaks of the past two and a half years, since the start of Israel’s genocide in Gaza, as a period where “several glass ceilings were broken.”

In the first eight months of the war, the US saw over 12,400 pro-Palestine protests, according to the Crowd Counting Consortium.

The Columbia University Gaza Solidarity Encampment inspired actions at around 180 universities worldwide, and in the UK, organisers reported more than 600,000 people marched in London for last May’s Nakba anniversary.

The unprecedented scale of public mobilisation has driven changes in divestment, academic freedom, and institutional ties to Israel’s military and financial networks.

Altikriti emphasises that the issue of Gaza has galvanised a “level of public awareness that we never had before and that we couldn’t even imagine before.”

Disunity as an obstacle facing Palestine solidarity movements

But Altikriti argues that momentum alone doesn’t guarantee outcomes — especially when movements are divided.

If governments are increasingly unwilling to lead on Palestine, and solidarity is the main arena of pressure, then the question becomes organisational: what kind of structure can hold a global movement together long enough to matter?

Scholars of social movements argue that fragmentation isn’t just disagreement — it’s what happens when activists pull in different directions, chasing parallel goals without a shared strategy, and losing political leverage as a result.

In the context of the Palestine solidarity movement, fragmentation can take the form of tactical splits — boycotting versus lobbying — as well as messaging: language, framing, or the priorities put forward.

With the political conversation amongst Western governments being driven by the debate of the post-war governance of Gaza, Altikriti argues, “One thing that unfortunately has been playing a divisive role within the global movement is the place of Palestinian politics.”

Academics, therefore, argue that disunity does not merely limit a movement’s effectiveness; it makes it easier for governments to proceed as though global mobilisation is temporary, incoherent, and ultimately containable.

The option of Trump-style diplomacy exemplified by the “Board of Peace” can be seen by Western governments as an acceptable solution when the alternative is dispersed activism with no shared strategy.

The Global Alliance for Palestine steps up

When asked about the thinking behind the formation of the GAFP, Dr Anas Altikriti said the idea was to “capitalise” on the growing support for Palestine by transforming the momentum into sustained political pressure.

Launched at a London conference in July 2025, the GAFP aims to “bring together civil society leaders, grassroots movements, and campaigners” with representatives from across dozens of countries and more than 60 organisations.

Its core mission is to “amplify and safeguard the global movement for Palestinian liberation by uniting fractured solidarity efforts into a coordinated international front”.

Among the alliance’s steering committee are international speakers including Jeremy Corbyn, Mustafa Baghouthi, Gerry Adams and Ronnie Kasrils.

The organisation has purposely decided not to invite any members of the Palestinian Authority or other politically aligned individuals to, Altikriti explains, “not have Palestinian politics be there from the start.”

The Secretary-General defines the GAFP as “an umbrella movement that doesn’t request or require organisations or campaigns to dissolve. In fact, the very opposite — that these organisations are strengthened, are empowered, are given the assets and information that are required so that they can improve and they can up their performances, but with a shared kind of coordination.”

To Altikriti and the founders behind the movement, unity does not equate to unanimity; the GAFP seeks to reinforce the local autonomy within these organisations while working towards a shared objective.

“We’re in a context that is becoming more and more vague, and hence more and more dangerous,” Altikriti tells The New Arab.

“As a result of that, we need to stay strong. We need to stay resolute. We need to be sure of where we stand and what we’re trying to achieve. Otherwise, we will be swaying and shifting, just like events around us and the world around us,” he adds.

“That’s not good for anyone or anything that we stand up for, because the next thing that will be swaying and will be shifting are our principles and our humanity, and that’s something that we can’t afford to do. All of a sudden, justice will become subjective. And things like oppression, racism, war crimes, will become matters of opinion.”

Trump’s proposed “Board of Peace” may be only one initiative among many, but it captures a wider reality: Palestine is still being discussed as a problem to be managed, rather than a people entitled to rights.

Since October 2023, global solidarity has disrupted that script — forcing Palestine into public view when governments preferred silence.

Whether that disruption becomes lasting political leverage may depend less on the scale of mobilisation than on its coordination.

For movements built on moral urgency, unity is no longer just a slogan. It is the difference between momentum that fades and pressure that endures.

Agnese Boffano is a journalist at The New Arab