Haidar Eid

Mondoweiss / June 16, 2022

Yara Hawari’s “The Stone House” is a story of unending Palestinian trauma rooted in the Nakba. However, it is also an expose of steadfastness, resistance, and I dare say – hope.

The Stone House

by Yara Hawari

96 pp. Hajar Press, £12.50

It happened that I was teaching my last classes of Literary Criticism, where I was discussing with my students literary terms such as realism and whether literature can transcend it and go “beyond realism,” so to speak, when I began reading Yara Hawari’s ‘novella’ The Stone House. But is it a novella, i.e. a literary genre that fictionalizes reality? I rarely finish reading fiction in one sitting, but this book was an exception.

In my other course about the genre, we read Palestinian and South African texts, by Ghassan Kanafani and Njabulo Ndebele, where we discuss history from the standpoint of the colonized and how it provides an alternative to the official, i.e. more dominant version history of the colonizer. We then compare Palestinian and South African history and conclude that Apartheid and Zionism both created a dominant historical narrative that sought to eliminate all other narratives.

This is why I found Yara’s (non)fiction amazing! Written/narrated from the perspective of three ‘characters’ representing three Palestinian generations from the 1920’s and 1930’s, then from 1948 (the Nakba generation) and then from 1968, after the Naksa, when all of historic Palestine fell into the hands of Zionist troops. The center of the novella, being a Palestinian story, is of course, the Nakba and its impact on Yara’s own father, grandmother, and great grandmother, narrated in a melancholic tone. In fact, being Palestinian myself, I would certainly say that it is my own family story told to me by my mother and grandmother in the form of hekaya, storytelling, our form of oral history that has kept our narrative alive despite all attempts by more hegemonic powers to erase it. In Yara’s novella it is sometimes told in a straightforward manner, and sometimes in the form of stream of consciousness, personal and collective.

Mahmoud, Yara’s father, is given the first chapter to let us know about the direct impact the Nakba had on his life, even though he was born a few years after it. Mahmoud is a second-class Palestinian citizen of Israel, living at the receiving end of Israel’s racist laws that, a “present absentee,” a constant reminder of Israel’s original sin, i.e. the ethnic cleansing of Palestine, and for that he has to pay a heavy price.

The second chapter is narrated by his mother, Dheeba; a brave, eloquent Bedouin woman married to a fellah (farmer/peasant) and having to deal with this fact in addition to being a Palestinian. Despite Dheeba being illiterate, the social and the political are discussed in a fascinating way through her consciousness.

The third chapter is given to Hamda, Yara’s great grandmother, who takes us back to the turn of the century when Palestine was first under Ottoman occupation, and then under the British colonialism that was naively welcomed by the Palestinians based on the false promise of freedom.

What connects all three characters, and the rest of the Palestinian people, is the Nakba. Edward Said expressed this very well in After the Last Sky, where he saw a line between the personal life of every Palestinian and the Nakba. The theme of almost all of Ghassan Kanafani’s writings revolve around that horrific event. Most of Mahmoud Darwish’s poetry is about Palestinian identity after the Nakba. And Naji Al Ali’s Handala is the son of the Nakba. Yara’s book is no exception.

… [Mahmoud’s] found that stories of the Catastrophe rested heavily and painfully on his mind. He could imagine them vividly, with anguish, as if they were his own memories. They overshadowed the present and blurred distinctions in time and between generations.

As if Yara was describing my own feelings!

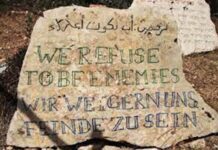

This a story of personal hekayas, of an unending trauma, the center of which is the Nakba. But at the same time, it is an expose of Sumud/steadfastness, muqawama/resistance, Thaakera/memory, Hawiyya/identity and. I dare say, HOPE!

This is why I have decided to conclude this review with a quote by Patrice Lumumba, the first democratically elected Prime Minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo:

“History will have its say one day. Not the history they teach in Brussels, Paris, Washington, [Tel Aviv] or the United Nations but the history taught in the country set free from colonialism and its puppet rulers.

Africa/[Palestine] will write her own history and it will be a history of glory and dignity.”