To advance its political, economic, and security goals, Israeli intelligence helped whitewash the murder of half a million members of the Indonesian Communist Party and other leftist groups in the 1960s.

Eitay Mack

+972 / September 9, 2019

In October 1965, the Indonesian government launched a massive purge of left-wing and communist parties in the country. Over the following six months, at least half a million members of the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) and related leftist parties were murdered, while more than one million citizens were imprisoned without trial. Many of those who were jailed were brutally tortured, held in inhumane conditions, or sentenced to hard labor. Some of them remained in prison for up to 30 years.

The official justification for the purge was a series of events that took place beginning on October 1, 1965. A group called the 30 September Movement, led by a commander from the Presidential Guard, kidnapped and murdered six generals; they claimed they were trying to prevent a CIA-backed military coup against Ahmed Sukarno, the democratically-elected president, who had been a hero of Indonesia’s liberation struggle from Dutch colonial rule.

A group of generals under the command of General Suharto claimed the murders were an attempt by the Communist Party and its leftist allies to take control of Indonesia by force with the help of China. The army took over the government and immediately launched a campaign of incitement that led to the massacres and mass detentions.

For decades the military regime insisted, as did various investigators, that those six blood-soaked months were the consequence of spontaneous actions carried out by ordinary citizens who were enraged at the left’s attempt to take over the country. Geoffrey Robinson, a UCLA professor who has dedicated his life’s work to researching the horrors in 20th century Indonesia, asserts in his book “The Killing Season: A History of the Indonesian Massacres, 1965-66,” that the army directed the killings and mass detentions via commando units that had been created specifically for this purpose.

Robinson found documents showing that the operations were carefully planned. He writes that the army’s incitement campaign called for the complete destruction of the communist parties and their supporters. He also asserts that most of the people who were killed were initially detained for interrogation, often because their names appeared on lists that were prepared by the army.

Army, police, and militia forces carried out arrests without judicial warrants. Detainees were taken in for interrogation, during which they were severely tortured. After interrogation, prisoners were divided into three categories based on their alleged level of involvement in the 30 September Movement. Some were transferred to penal colonies, detention facilities, and concentration camps under military command, while others were executed. Those on the list to be executed were transported in military vehicles to killing sites, or passed on to death squads or anti-communist militias. Bound and blindfolded, the detainees were shot at the edge of killing pits and buried, or they were cut to pieces by machetes and knives. Corpses and body parts were often thrown into wells, rivers, lakes, and irrigation canals. Decapitated heads and limbs were displayed on roads, in markets, and in other public places.

Unlike the genocides in Bosnia and Guatemala, the victims in Indonesia were not targeted for elimination because of their ethnic, religious, or national identity, but rather for their suspected political affiliation. Besides the Communist Party leadership and leaders of various other leftist groups, most of the victims were poor or middle class. They included laborers, teachers, academics, students, high school pupils, artists, writers and public workers. Most of these people had no connection to the abduction of the six generals, but the killings and mass imprisonment were carried out as collective punishment.

Documents found recently in U.S. and British archives show that both countries were fully aware of the slaughter and mass detentions. The U.S. and Britain encouraged the elimination of the Communist Party and supported General Suharto’s military dictatorship, which remained in power until 1998. American and British support for Suharto’s regime came not only in the form of military aid, but also in economic ties that were meant to send a message to the army that it was acting appropriately.

American and British support for the Indonesian Army came against the backdrop of the Cold War and the Vietnam War. The Communist Party in Indonesia was one of the biggest in the world: in 1965 it had approximately 3.5 million members, with about 20 million citizens involved in related organizations (women’s organizations, youth organizations, farmers, laborers, cultural leaders, and more).

The Americans and the British considered Ahmed Sukarno, the president of Indonesia, to be anti-American and anti-West. The United States, which was concerned about his connections with China and the USSR, acted in Indonesia as it did in Chile, where it helped undermine Salvador Allende’s socialist government and helped put Augusto Pinochet in power. The U.S. and Britain strengthened the army and militarism in Indonesia, and led a psychological war that was meant to create anti-communist hysteria to grow support for the right. According to Robinson, while no concrete evidence has yet been found of American and British participation in planning the violence that broke out in October 1965, there is absolutely no doubt that the two major powers took advantage of the opportunity to pursue their interests in Indonesia and in Southeast Asia.

Indonesia reinstated democracy in 1998, but the army still enjoys tremendous political power. After decades of indoctrination, with Suharto’s military regime claiming as official justification that the military takeover was a necessary defense against the threat of communism, initiatives to investigate the truth have been systematically blocked. Even today, years after the end of the Cold War, senior members of the army and the political parties still use the communist threat as a means of consolidating public support.

‘Indonesians are not yet ready for full democracy’

The Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs recently unsealed several documents in the state archives, which provide information regarding the relationship between Israel and Indonesia during the 1950s. The documents reveal that despite conflicting messages from the Indonesian government, the State of Israel saw Sukarno as a central obstacle to the building of a relationship between the two countries, adopted the worldview of the U.S. regarding the Cold War and the Sukarno government, and hoped it would be ousted.

Beginning in the mid-1950s, Israel and Indonesia had informal interactions on the subjects of defense and security, but these did not become formal diplomatic relations. Indonesia acceded to Arab pressure in excluding Israel from the April 1955 Bandung Conference, at which the Union of Non-Aligned States was founded.

Sukarno was then battling rebel groups in various Indonesian islands, some of which were supported by the United States as a means of undermining his government. The deputy head of the Israeli embassy at the Hague wrote a report on a December 12, 1957 meeting he had with the director of the Political Section at the Dutch foreign ministry. According to the report, the Dutch foreign ministry staffer said that most of the rebel groups in Indonesia were anti-communist, and that if the communists continued to gain influence on the central island of Java or in Jakarta, the rebellion against Sukarno would grow. The report concludes with the observation that the writer had the impression the Dutch government would not be upset to see the rebellion spread in the Indonesian islands.

According to telegrams that were sent by representatives of the Israeli foreign and defense ministries in February 1957, the Indonesians were interested in acquiring fighter planes from Israel. In a telegram dated February 28, Emanuel Zippori of the Asia Department at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs wrote that the Indonesian representatives did not seem to have specific instructions as to how to interact with Israel; in some countries the Indonesian representatives had good official and personal relations with their Israeli counterparts. It depended on the personality of the Indonesian representative.

In November 1957 the Ministry of Defense prepared a list of military equipment that it was prepared to sell to Indonesia, including light weapons. The condition for carrying out a sale was a legal signature from Indonesia, even if the deal was carried out through a proxy. In October 1958, Israel was asked to sell 9mm hand grenades to Indonesia. Israel asked and received consent from the Netherlands, which was at the time involved in a rivalry with Indonesia over control of the western part of New Guinea.

In a telegram dated April 15, 1958, Shmuel Bendor, Israel’s representative in Czechoslovakia, reported on a meeting with the Indonesian ambassador in Prague. According to Bendor, his Indonesian counterpart dismissed the United States’s claims and criticized its attitude toward Indonesia.

“They say Indonesia is heading toward Communism,” the Indonesian diplomat said. “That is foolishness. Indonesia does not want to belong to any side, because we do not believe that the world is divided into two sides, or that every country must choose a side to which it belongs. This is what the Americans do not want to understand. For example with regards to the weapons — they resent Indonesia’s attempts to acquire weapons from eastern Europe. Indonesia has no choice, because the Americans impose conditions that Indonesia cannot accept (and he spoke about financial aid).

“The ‘miserable’ (his term) Indonesian Army must acquire some new weapons, because the rebels use new weapons,” the diplomat continued. “They also claim that President Sukarno is sympathetic toward communism, which is absurd. He is a democrat in every sense of the word. If there is one aspect of his ideology that one could criticize, it is that he has a tendency to be too liberal. Indonesia needs a strong hand, because its people are not yet ready for full democracy. The various political parties place party politics above the national interest — this is also true of parties that are in the governing coalition — and this undermines the stability of the government. Sukarno knows this, but his liberal worldview prevents him from using a strong hand to deal with the matter.”

The Israeli government decided against selling arms to Indonesia for three reasons: Indonesia’s refusal to establish formal diplomatic relations with Israel; the difficulty in maintaining secrecy; and the risk that the sale would endanger Israel’s relations with other states in the region. In a telegram to the director of the Foreign Ministry dated April 11, 1958, Israeli diplomat Walter Eytan wrote: “The matter would not remain a secret, just as the deals with Nicaragua and Cuba did not remain a secret. Any sale of weapons to Indonesia would bring the enmity of important Asian states. Just as we saw in South America, other Asian states will approach us with similar requests and we will be in serious trouble, just as we got into serious trouble in Latin America.”

At a meeting of the Foreign Ministry on April 4, 1967, Foreign Minister Abba Eban summarized the relationship between Israel and Indonesia at that time: “We were looking for new leadership. We were able to reach out and discuss some practical matters that might allow Israeli representation in Indonesia, for some development and economic enterprises. Matters went back and forth and there were ups and downs. Everything was predicated on Sukarno being deposed.”

‘Do not treat them like Africans but as Europeans’

Foreign Ministry documents reveal that within several months of the massacres, the Mossad knew who was responsible. A report written on November 15, 1966, just six months after the massacres were carried out, describes the chain of events: “In October 1965, the communists tried to take over the government with the help of mainland China. The army succeeded in putting down the takeover attempt and the Communist Party was declared illegal.”

“The Indonesian Communist Party, which was the most powerful party in the country with three million members, under the leadership of D.N. Aidit, collaborated with the Chinese,” the report continues. “If the attempted coup had succeeded, China would have had a significant advantage that would have redistributed the power balance in the region. A mass slaughter of the participants in the uprising and of their families was carried out, with the victims numbering between 300,000 and 700,000. In March 1967 the army took over, under the leadership of General Suharto…”

In the same report, General Suharto is described as “[t]he acting prime minister, supported by the army and the anti-communists. Overtly pro-Western. An anodyne personality who is not well known among the people.”

In the 54 years since the massacres, details are still emerging as to the number of dead, who killed them and why, and what we can learn from the events that took place. The Mossad report is thus extremely important, since it confirms that there was indeed a slaughter of several hundred thousand citizens. The number of dead mentioned in the Mossad report matches the number that is generally agreed upon by most investigators, although the Mossad also adopted the propaganda of the Indonesian Army regarding the October events and the conspiracy theory about China. Today we know there is no evidence to support this version of the events.

After General Suharto took over, the Mossad managed Israel’s relationship with Indonesia. The knowledge of the massacres and who was behind them did not prevent the intelligence agency from building economic and security ties with the military regime in Indonesia, under the auspices of a classified initiative called “House and Garden.” Indonesia was given a code name for security reasons; occasionally, the name “South Korea” was also used. Foreign Ministry documents make it clear beyond a reasonable doubt that the reference could only have been to Indonesia.

The Mossad led contacts with the Indonesian military regime to initiate joint commercial projects such as crude oil, cotton, phosphates, beef, domestic aviation, trees, soya, paper, corn, metal barrels and oil transportation. Some of this commercial activity was managed via proxy companies. Similarly, the Indonesian army and Israel jointly created a company for the marketing of diamonds from Indonesia. On May 28, 1967, the Mossad closed a deal with an Indonesian company called Berdikari, which was controlled by army generals. The agreement specifies that the Indonesians were interested in acquiring military matériel and uniforms from Israel.

The Mossad organized visits for Indonesian officials to Israel, and in return Mossad representatives visited the military regime in Indonesia. The mutual visits were carried out according to utmost secrecy. According to the notes prepared by the Mossad ahead of a January 31, 1967 visit, “Members of the delegation will be introduced as visitors from South Korean. Do not mention their nationality unless you have coordinated in advance with Mossad representatives.” The document prepared by the Mossad on April 6, 1967 ahead of another Indonesian delegation’s visit specifies, “We know little about their character, way of thinking, or real relationship with us. Nevertheless, do not treat them like Africans but rather as though they were Europeans.”

The agenda for the visit included — besides meetings with the director of the Foreign Ministry and the head of the Mossad — a performance of King Solomon and a fashion show of Gottex bathing suits. On July 30, 1967, another delegation from Indonesia arrived in Israel. This one included director of the prime minister’s office, who was also the head of the security services. The delegation was interested in acquiring replacements for military equipment obtained from the USSR. They met with the head of the Mossad, the defense minister, and the IDF chief of staff, participated in an aerial tour of the Sinai Peninsula, and saw a display of military hardware at Tzrifin Military Base.

Since the Mossad managed relations with Indonesia and most of the documents from that period have not yet been released to the public, it is difficult to know how Israel grew its commercial and defense relations with Indonesia. The Indonesia example, however, illustrates the danger in the Mossad managing state-to-state relations, as it does today with many countries around the world — including Arab states. Despite their knowledge that the military regime of Suharto had massacred hundreds of thousands of citizens, the Mossad built economic and security ties with the Indonesian generals. Given this history, we cannot guarantee that today’s Mossad — which is essentially a secret institution that deals with security — takes human rights and international law into consideration.

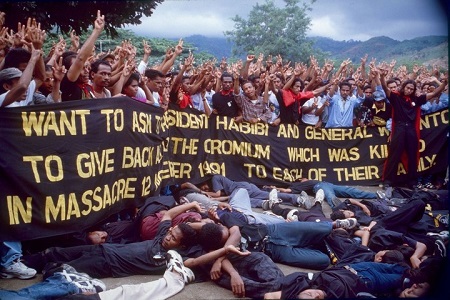

It is extremely regrettable that, just 20 years after World War II, like the United States and like most of the Western states, Israel participated in whitewashing the crimes of the Indonesian Army, and saw it as a legitimate partner for advancing political, economic, and security goals. The world’s silence in the 1960s, when hundreds of thousands of Indonesians were massacred or imprisoned indefinitely without trial, emboldened the military regime. In 1975 they used the communist threat as an excuse to invade East Timor; by the time the security withdrew in 1999, they had committed crimes against humanity — torturing, raping, and killing many civilians.

The Israeli Foreign Ministry and the Mossad have a moral obligation to disclose all their documents concerning Indonesia from those years, in order to help bring to light the truth, just as Israel expects other countries to disclose documents in their possession regarding the Holocaust.

Eitay Mack is an Israeli human rights lawyer working to stop Israeli military aid to regimes that commit war crimes and crimes against humanity