Lawrence Davidson

Consortium News / November 4, 2019

Ignorance in general, and ignorance of the Palestinian situation in particular, can be easily be exploited to the benefit of racism and oppression.

In the October 4 issue of Rolling Stone magazine it was reported that the 27-year-old “pop, pop-rock, and R&B” singer-actress Demi Lovato had made a trip to Israel in order to, among other things, be baptized in the Jordan River. Here is how she described it: “When I was offered an amazing opportunity to visit the places I’d read about in the Bible growing up, I said yes. … Spirituality is so important to me … to be baptized in the Jordan river—the same place Jesus was baptized—I’ve never felt more renewed in my life.”

The trip drew attention because it was financed by anonymous donors, reportedly in the amount of $150,000, and required her to allow posted reports of her experiences. Among those reports were these statements: “There is something absolutely magical about Israel” and “This trip has been so important for my well-being, my heart, and my soul. I’m grateful for the memories made and the opportunity to be able to fill the God-sized hole in my heart. Thank you for having me, Israel.”

There quickly followed a backlash from those who saw her trip as an endorsement of the state of Israel despite its apartheid nature. The criticism upset Lovato, and so, on an Instagram post, she tried to set things straight: “No one told me there would be anything wrong with going or that I could possibly be offending anyone, with that being said, I’m sorry if I hurt or offended anyone, that was not my intention. … This was meant to be a spiritual experience for me NOT A POLITICAL STATEMENT and now I realize it hurt people and for that I’m sorry.” This Instagram apology was deleted soon after posting—perhaps because it offended the anonymous parties that paid for her trip.

If you look at the rather sparse coverage of this incident, both here in the U.S. and in Israel, you will notice that the main question being considered by the media is, Who sponsored Lovato’s trip? Was it the Israeli Ministry of Jerusalem Affairs, some Christian Zionist outfit, or a combination of both? Actually, I don’t think it matters much. We know that the Israeli government is trying to break the worldwide boycott (BDS) by luring celebrities to visit the country. It is no doubt assisted in this effort by all manner of Zionist organizations, including the Christian Zionists. Putting aside the question of who paid for the trip, there is a much more interesting aspect of this affair—Lovato’s striking ignorance.

Public Knowledge

The struggle between Zionists and Palestinians has been going on for over 100 years, counting from the Balfour Declaration of 1917. The Zionist ideology which underlay the drive for a “national home for the Jewish people” in Palestine inevitably drew resistance from the Arab population — both Muslim and Christian — that had been resident there for thousands of years. And that resistance was met by a typically violent response from the European Zionist invaders pouring into the area under the protection of the British imperium. That violent response was one that had been honed by centuries of European imperialism operating worldwide. It involved a deeply racist disdain for the “natives,” the use of military forces to suppress and oppress, and the strict separation of the European colonizers and the indigenous population. When the British finally left Palestine in 1948, the Israeli settler state maintained traditional imperialist practices. It has never stopped. That makes Israel a functioning colonial state founded and maintained in the spirit of 19th century imperialism.

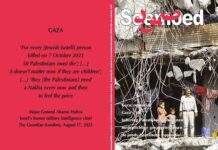

Today there are 7.2 million Palestinian refugees worldwide. Millions live in “59 refugee camps throughout the West Bank and Gaza Strip, Jordan, Syria and Lebanon”. The Gaza Strip, which is 140 square miles (363 square kilometers), is crammed with 1.8 million mostly displaced Palestinians held hostage to an Israeli blockade. Gaza is often referred to as the world’s largest open-air prison.

All of this, the history of Palestine and Israel, and the ongoing present situation, is public knowledge. For instance, here is a sample of stories to make recent headlines: In Israel racism is not just the right, it is the state (Haaretz, September 26, 2019); Israeli doctors and torture (972 Magazine, Oct. 7, 2019); Israeli army raids Palestinian NGO in an attack on human rights (Amnesty International, Sept. 19, 2019); Is Israel an ‘apartheid’ state? This U.N. report says yes (The Washington Post, March 16, 2017). And, let’s throw in this final piece just for its scientific shock value: Israeli teachers discouraged from teaching evolution (124 News, August 30, 2019).

This listing is but a proverbial drop in the bucket. In any given week there are tens of similar pieces appearing all over the world. Notice that most of the above sources are Israeli (Haaretz, 124 News, +972 magazine). Thus, even if all your information, left to right, comes from Israeli sources, you can’t help knowing that, to paraphrase a line from Hamlet, “something is rotten in the state of Israel.” Yet, apparently, Demi Lovato did not know. “No one told me there would be anything wrong with going or that I could possibly be offending anyone.” If we believe her, and I am inclined to do so, how can we explain such ignorance? It turns out that explaining it is not that hard.

A Natural Attention Zone

Most people pay attention to what immediately concerns them, both as relates to place and time. It is a logical and age-old orientation that no doubt evolved because it can provide immediate survival value. I call this phenomenon a natural attention zone, or, if you will, natural localism. In terms of territory, it translates into a familiarity with about 30 square miles around the place you live, work, study, and so forth. In the modern era, one can also virtually import points of particular personal interest into this attention zone from further away. For instance, American Zionists do this virtual import when it comes to Palestine/Israel. So do Palestinian Americans. However, if you have no reason to pay attention to a place, or you only pay attention to it in a highly selective way, you will not bother with seemingly superfluous information. You will just ignore it.

Given her spirituality, Demi Lovato seems to have imported Bible stories into her attention zone — or at least did so as a child — and this helped shape her consciousness. But it never seems to have gone beyond Sunday school piety, and even this was overtaken as she aged by the demands of a successful singing and acting career. Then came a seductive offer. When given the chance to travel to “the places I’d read about in the Bible” Lovato apparently became aware of that “God-sized hole in my heart” and, so to speak, hopped on the airplane no questions asked. She was no doubt too excited to recognize that her spiritual adventure warranted further investigation — that, in fact, someone was using her yearning for renewed spirituality for their own political/ideological purposes. She is not alone in this regard.

Millions of people go to Israel as tourists every year, and over half are religious Christians looking for the same “spiritual renewal” as Demi Lovato. They do so single-mindedly in a fashion that blinds most of them to the racist tragedy unfolding around them. Engrossed as they are in their Bible-centered attention zone, they never realize that their “renewing” pilgrimage legitimizes, and financially subsidizes, an apartheid state.

You might ask, with millions of devout Christians going yearly to Israel, why the seductive offer to Demi Lovato? One can only assume that her celebrity status was seen as a useful vehicle to push back the international boycott of Israel movement—and a further lure to her large fan base to follow her example.

Early in my tenure-track residency at West Chester University, my office computer was hacked by some anonymous Zionist source waging cyberwar against the free speech of those supporting the Palestinians. The way they did this was by rerouting several of my opinion pieces to literally thousands of random e-mail addresses. I called in the university IT folks and got the problem fixed within a few days.

In the interim, it was a pretty interesting experience. On the one hand, it was potentially free advertising for my point of view — the hackers seemed not to have grasped this potential. On the other, it taught me the probability was high that the random recipients would see this as an annoying intrusion into their attention zone, where the Palestinian-Israeli struggle was seen as irrelevant. A common reply was, “Please stop sending me these e-mails. I don’t know anything about this and I don’t care.”

And there we have it. Ignorance beyond one’s figurative 30 square miles is the default position. That opens most of us to all kinds of manipulation. Throw in an obsession with Bible stories and, as regards to Palestine/Israel, one’s vulnerability goes up. The alleged ancient “holiness” of the place neutralizes all of present Israel’s ongoing sins. Thus, ignorance in general, and ignorance of the Palestinian situation in particular, can be exploited to the benefit of racism and oppression. Demi Lovato is a recent example of this fact. When it comes to “Christian Tourism,” let the buyer beware.

Lawrence Davidson is professor of history emeritus at West Chester University in Pennsylvania; he has been publishing his analyses of topics in U.S. domestic and foreign policy, international and humanitarian law and Israel/Zionist practices and policies since 2010