David Hearst

Middle East Eye / May 15, 2020

In its current formulation, Israel knows only one direction: to deepen its domination over a people whose land it has stolen and continues to steal.

Anniversaries commemorate past events. And you could be forgiven for thinking that an event which happened 72 years ago is indeed in the past.

This is true of most anniversaries, except when it comes to the Nakba, the “disaster, catastrophe or cataclysm” that marks the partition of Mandatory Palestine in 1948 and the creation of Israel.

The Nakba is not a past event. The dispossession of lands, homes and the creation of refugees have continued almost without pause since. It is not something that happened to your great grandparents.

It happens or could happen to you anytime in your life.

A recurring disaster

To Palestinians, the Nakba is a recurring disaster. At least 750,000 Palestinians were displaced from their homes in 1948. A further 280,000 to 325,000 fled their homes in territories captured by Israel in 1967.

Since then, Israel has devised subtler means of trying to force the Palestinians from their homes. One such tool was residency revocations. Between the start of Israel’s occupation of East Jerusalem in 1967 and the end of 2016, Israel revoked the status of at least 14,595 Palestinians in occupied East Jerusalem.

A further 140,000 residents of East Jerusalem have been “silently transferred” from the city, when the construction of the separation wall started in 2002 blocking access to the rest of the city. Almost 300,000 Palestinians in East Jerusalem hold permanent residence issued by the Israeli interior ministry.

Two areas were cut off from the city although they lie within its municipal boundaries: Kafr Aqab to the north and Shu’fat Refugee Camp to the northeast.

The residents of neighbourhoods in these areas pay municipal and other taxes, but neither the Jerusalem municipality nor government agencies enter this territory or consider it their responsibility.

Consequently, these parts of East Jerusalem have become a no man’s land: the city fails to provide basic municipal services such as waste removal, road maintenance and education, and there is a shortage of classrooms and day-care facilities.

The water and sewage systems fail to meet the population’s needs, yet the authorities do nothing to repair them. To get to the rest of the city, residents have to run the daily gauntlet of the checkpoints.

Another tool of expropriation is the application of the Absentee Property Law, which, when passed in 1950, was intended as the basis for the transfer of Palestinian property to the State of Israel.

Its use was generally avoided in East Jerusalem until the construction of the wall. Six years later, it was used to expropriate “absentee land” from the Palestinian residents of Beit Sahour for the construction of 1000 housing units in Har Homa, in South Jerusalem. But generally its purpose is to provide a mechanism for “creeping expropriation”.

A Nakba in real time

The centrepiece of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s election campaign and the central legislative purpose of the current Israeli unity government would constitute another chapter of dispossession for Palestinians in 2020. Those are the plans to annex one third – or at worst two thirds – of the West Bank.

Three scenarios are currently under consideration: the maximalist plan to annex the Jordan Valley and all of what the Oslo Accords referred to as Area C. This is about 61 percent of the territory of the West Bank which is administered directly by Israel and is home to 300,000 Palestinians.

The second scenario is to annex the Jordan Valley alone. According to Israeli and Palestinian surveys conducted in 2017 and 2018, there were 8,100 settlers and 53,000 Palestinians living on this land. Israel split this land into two entities: the Jordan Valley and the Megillot-Dead Sea regional council.

The third scenario is to annex the settlements around Jerusalem, the so-called E1 area, which includes Gush Etsion and Ma’ale Adumin. In both cases Palestinians who live in the villages around these settlements are threatened with expulsion or transfer. There are 2600 Palestinians who live in the village of Walaja and parts of Beit Jala who would be affected by the annexation of Gush Etsion, as well as 2000-3000 Bedouins living in 11 communities around Ma’ale Adumin, such as Khan al-Ahmar.

What would happen to Palestinians who live on land that Israel has annexed?

In theory they could be offered residency, as was the case when East Jerusalem was annexed. In practice, residency will only be offered to a very select few. Israel will not want to solve one problem by creating another.

Most of the Palestinian population of the areas annexed would be transferred to the nearest big city, as happened with the Bedouins in the Negev and East Jerusalemites who find themselves in areas cut off from the rest of the city.

The generals’ warning

These plans have generated expressions of horror amongst Israel’s security establishment, that has grown used to being listened to, but who now wield less influence over policymaking than they once did.

This is not because the former generals hold any moral objection to expropriation of Palestinian land or because they think Palestinians have a legal right to it. No, their objections are based on how annexation could imperil Israel’s security.

A fascinating resume of their thinking is provided by an open-source document published anonymously by the Institute for Policy and Strategy (IPS) in Herzliya. They state that annexation would destabilise the eastern border of Israel, which is “characterised by great stability, a quiet and a very low level of terror”, and that it would cause a “deep jolt” to Israel’s relationship with Jordan.

“To the Hashemite regime, annexation is synonymous with the idea of the alternative Palestinian homeland, namely, the destruction of the Hashemite kingdom in favour of a Palestinian state.

“For Jordan, such a move is a material breach of the peace agreement between the two countries. Under these circumstances, Jordan could violate the peace agreement. Alongside this, there may be a strategic threat to its internal stability, due to possible unrest among the Palestinians in combination with the severe economic hardship Jordan is facing,” the IPS document says.

That would only be the start of Jordan’s problems with annexation. Even a minimalist option of annexing E1 – the area around Jerusalem – would sever East Jerusalem from the rest of the West Bank, endangering Jordan’s custodianship of Islamic and Christian holy sites in Jerusalem.

Annexation would also lead to the “gradual disintegration” of the Palestinian Authority, the IPS claims.

Again, there is no love lost here. What concerns the Israeli analysts is the burden that would be placed on the army. “The effectiveness of security cooperation with Israel will deteriorate and weaken, and who will replace it? IDF! Forcing many forces to deal with riots and order violations and the maintenance of the Palestinian system.”

The security establishment goes on to say that annexation could trigger another intifada, strengthening the idea of a one-state solution “which is already acquiring a growing grip in the Palestinian arena”.

The Saudi factor

In the wider Arab world, the paper notes that Israel would forfeit many of the allies it believes it has made in Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Oman and intensify the BDS campaign internationally.

Saudi Arabia’s role in dousing the flames of Arab reaction to Netanyahu’s annexation plan was specifically mentioned in Israeli security circles recently. The Saudi support for any form of annexation was deemed crucial.

True to form, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s regime has been trying to soften Saudi hostility to Israel in the media and particularly television drama. A drama called Exit 7 produced by Saudi Arabia’s MBC TV recently contained a scene of two actors arguing about normalisation with Israel.

“Saudi Arabia did not gain anything when it supported Palestinians, and must now establish relations with Israel….The real enemy is the one who curses you, denies your sacrifices and support, and curses you day and night more than the Israelis,” one character says.

The scene produced a backlash on social media and eventually a fulsome statement of support for the Palestinian cause by the Emirati foreign minister.

The attempt demonstrated the limits of Saudi state mind control, which will be weakened still further by the drop in the price of oil and the advent of austerity across the Arab world.

The future Saudi king will no longer be able to buy his way out of trouble.

The Committee

It is worth repeating again that the motive for enumerating the destabilising effects of annexation is not some inherent disquiet at the loss of property or rights. The security establishment’s central concern stems from the possibility that Israel’s existing borders could be imperilled by overreach.

For similar reasons, a number of Israeli journalists have forecast that annexation will never happen.

They could be right. Pragmatism could win the day. Or they could be underestimating the part that nationalist religious fundamentalism plays in the calculations of Netanyahu, David Friedman, the US ambassador, and the US billionaire Sheldon Adelson, the three engineers of the current policy.

While the US role as “an honest broker” in the conflict has long been exposed as a sham, this is the first time I can remember that a US ambassador and a major US financier make more zealous settlers than a Likud prime minister himself.

Friedman is chairman of the joint US-Israel committee on settlement annexation which will determine the borders of post-annexation Israel. This committee is meaningless in international terms, as it has no representation of any other party to the conflict, let alone the Palestinians whose leaders have boycotted the process.

Two separate sources from the joint committee have told Middle East Eye that it is leaning towards a once and for all expansion of Israel in the West Bank, and not an incremental one. One source said that it will go for the whole of Area C – in other words the maximalist option.

Again they could be wrong. Both say the annexation that is chosen will tailor itself to the contours of Donald Trump’s “Deal of the Century” which reduces the current 22 percent of historic Palestine down to a group of bantustans scattered around Greater Israel.

The climax

The Nakba, 72 years old today, continues to live and breathe venom. The Nakba is not just about original refugees but their descendants – today some five million of them qualify for the services of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNWRA).

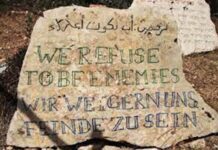

Trump’s decision to stop funding UNWRA, and Israel’s insistence that only the original survivors of 1948 should be recognised, has sparked an international campaign in which Palestinians sign a declaration refusing to relinquish their right of return.

“My right of return to my homeland is an inalienable, individual and collective right guaranteed by international law. Palestinian refugees will never yield to the ‘alternative homeland’ projects. Any initiative that strikes at the intrinsic foundations of the right of return and negates it is illegitimate and null, and does not represent me in any possible manner,” the declaration says.

Significantly it was launched in Jordan, another sign that feelings are running high there.

The Israeli security assessment that a two-state solution is dead in the minds of the majority of Palestinians is surely correct. Most Palestinians see annexation as the climax of the Zionist project to establish a Jewish majority state, and confirmation of their belief that the only way this conflict will end is in its dissolution.

But by the same token, the annexation plans under discussion should be proof to the international community, if one were needed, that far from being a country living in fear, and under permanent attack from irrational and violent rejectionists, Israel is a state which cannot share the land with Palestinians, let alone tolerate Palestinian self-determination in an independent state.

In its current formulation, Israel knows only one direction: to deepen its domination over a people whose land it has stolen and continues to steal.

David Hearst is the editor in chief of Middle East Eye