Ramona Wadi

Middle East Monitor / March 20, 2021

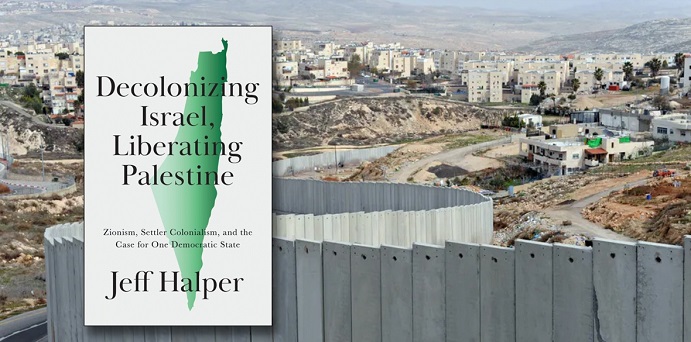

‘The two-state solution has always been merely a cynical tool of conflict management never intended to actually resolve the conflict.” Jeff Halper’s succinct statement regarding international diplomacy over the loss of Palestine and Israel’s colonial expansion provides the premise of Decolonising Israel, Liberating Palestine. International diplomacy has failed because it refuses the solution that lies in decolonisation.

A one-state already exists, Halper argues. The question is how to transform a settler-colonial, apartheid state into a secular democratic state for all its citizens. An anti-Zionist Israeli citizen and activist, Halper argues that the Palestinian narrative must be prioritised in terms of anti-colonial struggle, as must the settler-colonial population engage with the colonised by recognising their implicit role in Palestine’s appropriation.

Halper clarifies that the book is an Israeli analysis of settler-colonialism. “This is not a book a Palestinian would write, but hopefully, it is one a Palestinian would find useful.” This statement recognises the importance of distinguishing between Palestinian and Israeli narratives, making space for the former, while including the latter as an accompaniment rather than an imposition.

Tracing the logic of colonisation and dispossession, Halper argues that decolonisation needs to start from the colonial situation itself. Colonialism is described as “unilateral”, hence the importance of recognising indigeneity, and to ensure that the non-indigenous participation in decolonisation – the settler-colonial population – does not appropriate indigeneity.

Halper writes: “A settler project does not want to determine its final borders until all the ‘unbounded territory’ is finally incorporated physically and legally.”

Bolstered by the European settler-colonial status, as well as the legitimisation of the Zionist settler-colonial project within the international arena, Israel has been able to ascertain its presence through several forms of violence, which the book discusses in detail, within a backdrop of political implications for the Palestinian people.

Tracing the roots of “foundational violence” – the colonial dispossession of the indigenous population – Halper weaves an intricate description of how Jewish entitlement and the internationally-bestowed legitimacy upon the colonial project were aided and abetted by the United Nations (UN), which he writes: “Knowingly entrusted the fate of an entire people to a settler movement declaring its exclusive entitlement to the country, and its readiness to employ violent conquest and transfer.”

The gradual shift from anti-colonial resistance to diplomacy by the Palestinians sustained the two-state compromise for Israel’s benefit. Halper’s analysis contends that the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) knew that a two-state wouldn’t materialise, yet its pragmatism also legitimised Israel’s presence. The ongoing territorial loss, economic restrictions and Palestinian de-development were also used by the international community against the colonised. Subjugated to a neoliberal economy, Palestinian society fragmented further due to international institutions’ decision to prioritise the occupied West Bank over Gaza in terms of development, albeit still under Israeli control.

Meanwhile, the Oslo Accords deepened Israel’s security narrative and the Palestinian Authority’s collaboration with Israel. On an economic level, deprivation among the population led a percentage of Palestinians to become informers for Israel. With all components supporting Israel’s security narrative, thus legitimising the concept of conflict, the real issues of settler-colonialism was marginalised.

Yet, Halper writes that Zionism’s failure to completely eliminate the Palestinian population only leaves decolonisation as the way forward. Since the 1880s, the author notes, Palestinians have been actively engaged in everyday resistance, or sumud. The rights-based approach, which is what the Palestinians have included in their anti-colonial struggle, is jeopardised by the fact that settler-colonialism is not included in the UN Declaration on Granting Independence to Colonial Countries. The legal and political pathway to decolonisation, therefore, needs to be addressed, more so due to the fact that the one-state is still not considered an option, let alone the way forward.

The book’s discussion of the ten-point programme by the One Democratic State Campaign makes some vital points that can be contrasted with the obsolete two-state compromise that has facilitated Zionist colonial expansion. The restitution of land, along with the recognition and implementation of the Palestinian right of return, which Halper determines is feasible based upon Palestinian researcher Dr Salman Abu Sitta’s extensive mapping of Palestinian colonised territory, show the flaws in the two-state compromise, while strengthening the author’s claim that the international community has focused on managing the “conflict” to detract attention away from settler-colonialism.

Decolonisation would bring about a “regaining of sovereignty” for the Palestinians. In fact, the prioritising of Palestinian rights and narratives would bring the Israeli settler-colonial population to face colonial crimes as the foundations upon which reconciliation may take place. Halper’s advocacy for reconciliation after justice and acknowledgement would form the basis of inclusion of the indigenous and settler society in a single, democratic state. The end of colonialism, Halper writes, would be the call of the indigenous population.

The need for decolonisation is a direct confrontation to the two-state compromise. It also encourages reflection on the rights-based approaches adopted by the international community, ostensibly in favour of the Palestinian people, which nevertheless legitimise the “conflict” narrative by adopting the two-state paradigm as a purported solution.

Implementing the single democratic state, of course, will require reckoning by both Israelis and Palestinians, yet it is the former that needs to contend with the legacy of violence that founded the colonial state and its ongoing expansion.

Halper’s book is informative, offering an in-depth perspective that is lacking and addresses the concept of memory within the political framework of decolonisation. How far the concept will go, however, depends heavily on an absolute negation of the two-state compromise and the willingness to change the narrative from “there is no Plan B” to offering only the Plan B as a just solution.

Ramona Wadi is an independent researcher, freelance journalist, book reviewer and blogger; her writing covers a range of themes in relation to Palestine, Chile and Latin America