Asa Winstanley

Middle East Monitor / November 21, 2020

At the start of this year, in this column, I argued that the annexation of the West Bank was coming, one way or another.

The West Bank and the Gaza Strip were the remaining 22 per cent of historic Palestine left for the Palestinians in 1949, after the ceasefire between Israel and the Arab states.

Between 1947 and 1949, Zionist militias and then the newly-founded Israeli army (the former flowed into the latter) forcibly expelled some 800,000 Palestinians.

This massive act of ethnic cleansing – the Nakba – was the founding act of the state of Israel. It was the only way to establish a Jewish state in a country whose population, only two generations earlier, had consisted of 95 per cent indigenous Palestinian Arabs.

Jewish people were always a minority in Palestine. It was only after the intervention of the British Empire that the Zionist movement’s colonial project was imposed on the country from 1917 onwards.

One result of Israel’s illegal expulsion of the Palestinians in 1948 was that a Jewish majority had been gerrymandered in the country for the first time, using extreme violence and colonial oppression.

Today, that fleeting Jewish majority has long disappeared. Palestinians are once again the majority between the river and the sea.

In 1967, Israel launched another violent war of aggression against the Palestinian people and the neighbouring Arab states, illegally occupying the remaining 22 per cent of the land of Palestine. Another wave of forced expulsions of Palestinians followed.

In the decades since, Israel has been gradually annexing more and more Palestinian land. Palestinian communities are destroyed, bulldozed, and erased so that Jews-only settlements, “nature parks” and apartheid roads can be built on the ruins.

Israel has always operated according to the principle of “maximum land, minimum Arabs”.

It is for this reason that Israel has only been able to slowly annex the West Bank.

From the Zionist perspective, there’s little gained in removing Palestinians from their land unless there are new Israeli settlers ready to take their place. Otherwise, the Palestinians will be able to gradually return.

Over the course of more than 123 years, the Palestinian people have stubbornly refused to admit that they are a defeated people and have thus, through the sheer force of their collective will to resist, remained undefeated. They are killed and expelled, but keep on returning.

The majority of the world’s Jewish peoples have also stubbornly refused to bow to Zionism’s dictations. Most have refused to leave their native countries in order to make an imagined “return” to Palestine, so as to become colonial settlers and displace the indigenous people in the process.

The Zionist project had the infamous twin practice of the “conquest of land” and the “conquest of labour”.

Palestinian workers were not only expelled from their lands by the Zionist militias (even in the pre-Nakba colonial period) but were also denied jobs – a major reason for the explosion of the Palestinian Arab uprising that began in 1936 against the British occupation and the European-Zionist colonial settlers.

“Conquest of land” was married in “labour Zionist” ideology with the racist concept of “Hebrew labour” – meaning only Jews were allowed to work and live in the new colonial Jewish settlements. Israel’s racist Histadrut trade union federation excluded Palestinian Arabs well into the late 1950s.

But there was also a third, lesser-known “conquest” – what Theodor Herzl at the second Zionist congress in 1898 called “the conquest of communities”.

This meant a march through the institutions of the European Jewish communities’ representative organisations, with the goal of taking them over on behalf of the Zionist movement. This process took many long decades, but it was eventually quite successful.

That is why today in the UK, the Board of Deputies of British Jews (which was anti-Zionist until 1939) feels able to shamelessly claim to be almost the sole legitimate representative of a supposedly monolithic entity it likes to call “the Jewish community” – despite the fact that it views its primary role in public life to “lobby unashamedly for Israel.”

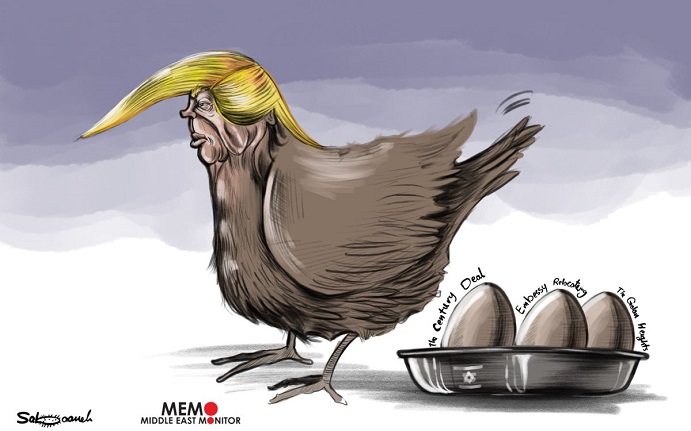

This is the relevant historical background with which to understand Trump’s so-called peace plan and the Israeli plot to annex the vast majority of the West Bank.

Earlier this year, those plans looked imminent. But there was a change of heart, and it was deemed politically inconvenient – at least for the time being.

But now, in the dying months of the Trump presidency, it appears that Israel has another window to advance its maximalist, expansionist vision.

Trump’s Secretary of State Mike Pompeo – a former CIA director – announced this week that a whole slew of human rights, campaigning and activist groups that support Palestinian human rights would be decreed “anti-Semitic”, simply for the supposed crime of opposing Israeli abuses and racism.

It’s a major parting shot, albeit one unlikely to hold up, either in the court of public opinion or in the real courts.

Will Trump also use this window to push Israel to enact its plans to annex most of the West Bank? Some pro-Israel analysts think it’s a distinct possibility.

Asa Winstanley is an investigative journalist living in London who writes about Palestine and the Middle East