Karim Makdisi

PassBlue / July 22, 2204

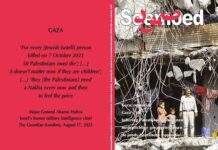

Against the backdrop of Israel’s genocidal war on Gaza and its officially sanctioned extremist settler recolonization assault in the occupied West Bank, the alarming escalation between Hizbullah and Israel over the last several weeks threatens to dramatically expand the regional war that has been simmering for nine months.

While the expansion of a Mideast war remains unlikely — given the stated reluctance of Hizbullah and the United States as well as Israel’s inability to fight on many fronts at once — the possibility cannot be dismissed. It’s clear that Israel needs to distract the world and people at home from its failure to achieve its declared objectives in Gaza to eradicate Hamas. Moreover, it is no secret that Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu will do whatever he can to stay in power by blocking a Gaza ceasefire and keeping his country at war.

Fears by the United Nations and warnings of potential “miscalculation” triggering such a wider clash miss the point: since Hizbullah and Israel’s last major war, in 2006, created mutual deterrence, both sides know exactly how far they can push each other before provoking a major conflict. Although Hizbullah and the Israelis are edging past previously held respective red lines, neither have yet gone past the point of no return.

In the short term, US-mediated efforts based on a return to UN Security Resolution 1701, which created a relatively successful cessation of hostilities since the 2006 war, is the only realistic alternative to an expanded war. This mediation, however, will fail until a permanent Gaza ceasefire is in place. But Netanyahu is rejecting such action in his insistence on a “total victory” against Hamas, which is not possible given Hamas’s steadfastness and Israel’s poor military performance in Gaza.

In the longer term, however, war seems inevitable. The consolidation of power of extremist forces in an increasingly isolated Israel, the long history of bipartisan US policy denying Palestinian self-determination and imposing conditions of surrender on them and the growth of Palestinian and regional resistance abilities underscore the urgent need for a regional settlement centered around Palestinian liberation and international law.

Lebanon’s southern front

While Hizbullah was not privy to details of Hamas’s Oct. 7, 2023 operation, for the first time in its history and in coordination with its regional allies among the Axis of Resistance, Hizbullah opened a second front with Israel on Oct. 8 in solidarity with Palestinians. The front attacked Israeli military positions in Israeli-occupied Shebaa farms to divert Israeli military assets and personnel to the north, away from the country’s anticipated war against Hamas in Gaza.

Hizbullah’s stated “red line” for keeping the scope of this front limited was and remains the position that Hamas cannot be allowed to be fully defeated. That will not happen, given Hamas’s steadfastness and the increasingly frantic calls within Israel’s army, low on morale and confused about governmental plans, to reach a ceasefire.

During the first few weeks of the Israeli-Hizbullah battle, attacks were concentrated near the border, or what the UN calls the disengagement Blue Line, established following Israel’s withdrawal in 2000 from southern Lebanon after nearly two decades of occupation. Hizbullah focused on weakening what its leader Hasan Nasrallah termed Israel’s “eyes and ears” by targeting its drones, sensors and other intelligence infrastructure, while Israel deployed weaponized drones to target Hizbullah fighters and destroy border towns. Tens of thousands of people were displaced on both sides of the border.

Still, the rules of the game and the mutual deterrence established after Israel’s large-scale but failed war in 2006 in Lebanon and mostly respected by both sides for 17 years, just about held out for several months after Oct. 8. This was despite that, according to the UN, Israeli cross-border “projectiles” — strikes — occurred at nine times the rate of those from Lebanon.

By early 2024, however, Israel started significantly escalating strikes. Most notably, it increased the targeting of civilians and assassinated Hamas’s deputy political leader, Salah al-Arouri, in Beirut. Hizbullah responded with unprecedented attacks on the strategic Meron and Safad military bases deeper into Israel. These actions set a pattern.

In recent weeks, the military and psychological exchanges have been ratcheted up intensively as pressure is mounting on Netanyahu to end Israel’s disastrous Gaza war and accept a ceasefire and exchange of hostages on both sides. The battles between Hizbullah and Israel now account for their fiercest fighting since the 2006 war.

With some high-level Israeli politicians and extremist settler pressure groups calling for war and even occupation or annexation in Lebanon, Israeli Defense Minister Yoav Gallant vowed — not for the first time — to return Lebanon “to the Stone Age,” and Israel’s education minister, Yoav Kisch, said that “Lebanon as we know it will cease to exist.”

A recent poll revealed that 62 percent of Jewish Israelis support an attack on Hizbullah. The Israeli army just approved operational plans to conduct an offensive and is readying itself for war on Lebanon, with Netanyahu pledging to redeploy forces from Gaza to its northern border.

Meanwhile, Israel is pre-empting negotiations to de-escalate tensions in Lebanon by trying to create a “new reality” on the ground, including extensive use of white phosphorus across the south. Israel’s goal is to carve out a five-kilometer “dead zone” in Lebanon along the Blue Line to render the area totally uninhabitable for civilians and fighters, even after a ceasefire in Gaza. Israel has now killed 300 Hizbullah fighters and continued its campaign to assassinate senior Hizbullah military commanders, with a third hit on July 3 murdering senior-ranking Mohammad Neameh Nasser.

Hizbullah has made it clear that the days are over when Israel dictates reality on the ground and its policy of “mowing the grass.” Hizbullah will not allow its hard-won deterrence to be compromised, including by ensuring that the war theater comprises large parts of Israeli territory and not just Lebanese, as has traditionally been the case.

The group has progressively revealed its increasingly sophisticated arsenal, including a potential game-changer in accurate air defense missiles that challenge Israel’s hitherto total air supremacy. Hizbullah has now downed advanced Israeli drones, and for the first time has forced Israeli aircraft to retreat from Lebanese airspace. It has also retaliated against Israel’s assassination of its commanders by launching unprecedented cross-border missile strikes. On July 6, Hizbullah launched the greatest number of strikes into Israel in a single day and its largest-ever air operation targeting Israeli bases in Mount Hermon.

Hizbullah also released a dramatic nine-minute video taken by reconnaissance Hudhud drones (named after Israel’s national bird) that undermined Israeli air defense systems and traveled unimpeded at low altitude across large swaths of the country. The drones took high-resolution color images of strategic military and industrial sites and settlements all the way to Haifa. Hizbullah media then released what it called a second episode of “The Hudhud,” covering the occupied Golan Heights. It ended the video by previewing the third episode, over Tiberias.

In a speech, Hizbullah leader Hassan Nasrallah clarified that Israeli politicians understood the meaning of this drone footage and that if Israel expanded its war in Lebanon there would be “no restraint and no rules and no ceilings” and “nowhere safe from our missiles and drones,” he said.

Escape hatch: expanding Resolution 1701 and US mediation

Yet, a broader conflict between Hizbullah and Israel still remains remote. Hizbullah has repeatedly made clear that it does not desire a war and the US has done likewise, particularly since its assessment of the situation for months has showed that Israel cannot win such a battle. Senior Israeli politicians have also begun toning down their rhetoric, signaling they would accept a negotiated settlement.

The only escape hatch to stop a conflict is a return to the vague terms outlined in UN Security Council Resolution 1701. It contains various de-escalation mechanisms, including indirect contact between the Israeli and Lebanese armies via UN-mediated “tripartite” meetings.

The resolution’s main objectives are to oversee Israeli withdrawal from all occupied Lebanese land, support Lebanon’s assertion of full sovereignty in the south and ensure there are “no weapons without the consent of the Government of Lebanon.”

To implement these terms, 1701 greatly enhanced the scope, strength and number of UN peacekeepers — UNIFIL — deployed in southern Lebanon, from the Litani River to the Blue Line, since Israel’s first invasion in 1978 and throughout its two-decade occupation since its second incursion in 1982.

Working with the Lebanese armed forces and with Hizbullah’s blessing, UNIFIL oversaw relative calm along the Blue Line for 17 years, until Oct. 8, 2023. Since then, its military units have largely been confined to observing and reporting violations and cross-border attacks, while only core civilian staff members report to work at headquarters in the border town of Naqoura. No tripartite meetings have been held during this period.

UN Secretary-General António Guterres and the UNIFIL force commander, Lieut. Gen. Aroldo Lázaro Sáenz, have joined the Lebanese government in urgently calling for a political solution based on full implementation of 1701. However, the resolution’s success until 2023 was premised on both sides being allowed to interpret the resolution according to their own narratives after the 2006 war while accommodating their shared interests in preventing escalation.

So, the question is, what does “full implementation” of 1701 exactly mean to each side, in light of possible shifts in their respective perceived interests and deterrence abilities amid the war in Gaza?

For Israel, 1701 requires having Hizbullah disarmed and expelled from southern Lebanon and creating a de facto “demilitarized buffer zone.” Until then, it sees itself having the right to “act freely” in self-defense. Israel has long wanted 1701 to provide UNIFIL a strengthened enforcement mandate and to adopt a more aggressive role in its area of operation rather than relying on the Lebanese army, UNIFIL’s main interlocutor on the ground, according to 1701.

For the Lebanese government, carrying out 1701 means Israel’s withdrawal from all remaining occupied land along the Blue Line and international guarantees to ensure Israel no longer violates Lebanese sovereignty — particularly its airspace — with impunity as it has done since 2006 with over 30,000 recorded breaches. For the government, 1701 also means strengthening the Lebanese army and ensuring there are no weapons placed in southern Lebanon without governmental approval.

Lebanon has affirmed, however, that it retains the right of resistance and that carrying out 1701 requires a ceasefire in Gaza. Lebanon’s government coordinates its official position with Hizbullah, which is also an important Lebanese political party.

Amos Hochstein, the US special envoy mediating tensions between Hizbullah and Israel, successfully brokered the 2022 Lebanese Israeli maritime boundary agreement. His current mediation includes working with the French, who are notably in a more peripheral role, while the UN is mostly sidelined.

Before the recent escalation, Hochstein, who was born in Israel and served in its armed forces, presented draft terms to Hizbullah through the powerful Lebanese speaker of Parliament, Nabih Berri. Berri is the long-time interlocutor between the US and Hizbullah and led the maritime deal negotiations with Hochstein.

Hochstein essentially proposed a return to the terms of Resolution 1701 as it had been practiced since 2006 — where Lebanon’s army takes up key positions in the south, Hizbullah’s armed presence is hidden (not withdrawn) and Israel stops its (visible) air violations over Lebanon — while involving an increased US role.

Importantly, Hochstein dispensed with some of his original key sticking points: most notably, removing the insistence on the withdrawal of Hizbullah forces up to at least 10 kilometers from the Blue Line, per Israeli demands.

As Berri told him, given that Hizbullah fighters are drawn from villages and towns across southern Lebanon, ” … It’s easier to relocate the Litani River further south than to displace Hezbollah northward.”

Hochstein’s main impetus is to conclude a three-phase “comprehensive” agreement “ready to go,” essentially giving Israel a face-saving path to accept a ceasefire with Hizbullah and pacify domestic pressure. The first two phases comprise a security deal allowing the return of displaced people on both sides and an aid package to strengthen Lebanon’s armed forces (recruiting, training and equipping) and to boost Lebanon’s economy and infrastructure.

The final phase in Hochstein’s plan entails defining a land boundary and creating for the first time “a recognized border” between the two countries. The plan’s novelty is that rather than going through the UN and its tripartite mechanism, the negotiations would be done by exchange of papers between Lebanon and Israel and renewed rounds of shuttle diplomacy by Hochstein. The proposal aligns with the role he played in the maritime border negotiations in which Hizbullah played a major part, albeit unofficially.

Hizbullah has not rejected Hochstein’s terms and continues to negotiate through both Berri, representing the Lebanese government, and French and Qatari mediators.

Meanwhile, negotiations for UNIFIL’s annual August mandate renewal by the Security Council have informally begun, with France — as the “penholder” — unrealistically floating a type of Lebanese army special forces unit to operate in southern Lebanon. Otherwise, UNIFIL does not expect major changes during the renewal talks.

It should be noted that Western — US, British and French — proposals and substantial aid since 2006 to boost Lebanon’s armed forces to allow them to play a meaningful role in southern Lebanon have mostly been disingenuous. The proposals’ intent and aid were meant to drive a wedge between the army and Hizbullah, who otherwise coordinate closely in southern Lebanon, and to ensure the army can never be provided the defensive weapons it needs to protect its borders from Israeli attacks.

Indeed, Israel’s Western partners have focused on creating a functionally demilitarized southern Lebanon with a symbolic but poorly equipped army providing a veneer of sovereignty.

Two core problems and the war to come

Regional and international consensus exists on the need to de-escalate the Lebanese-Israeli front, and Hochstein’s plan — with the safety crutches of Resolution 1701 and UNIFIL — offers a short-term path, but with the rapid departure of US President Biden, this route will become uncertain.

Yet, two core issues persist that the Israelis, Hochstein and other Western mediators do not fully grasp or accept.

First, Lebanon cannot be separated from Gaza in the short term. Hizbullah has repeatedly rejected US demands to effectively separate the Lebanese Israeli front from Gaza. For Hizbullah, closing its front with Israel before a permanent ceasefire is reached in Gaza is a nonstarter. To be sure, there is a huge internal divide among Lebanese regarding Hizbullah’s role, with some opposition parties accusing it of dragging Lebanon into a war. However, these groups have little impact on Hizbullah’s military actions and are incapable of shifting Lebanon’s official policy.

The second issue is that in the long-term, Gaza and southern Lebanon cannot be separated from the larger question of Palestine. Hamas’s Oct. 7 operation against Israel is a watershed moment for Palestinians in their struggle for self-determination and liberation regardless of what day-after scenarios the US plots. Hamas and the idea of resistance are now more popular than ever among Palestinians.

Hizbullah’s opening a second front on Oct. 8 represents the implementation for the first time of a “unity of front” strategy among the Axis of Resistance members, coordinated by Hizbullah, from Iran and Yemen to Iraq and Lebanon.

Israel, on the other hand, is more insecure and reliant on the US than ever before. Without continuous weapons supply and diplomatic support from the US — widely seen in the Arab world as the main threat to regional peace and stability and a co-belligerent in the Gaza war — Israel would have ended its war months ago. The country is also more globally isolated, its economy has been battered and it faces accusations of “plausible genocide” in Gaza by the International Count of Justice and the UN. It is also accused of practicing apartheid by the UN and major human rights organizations.

The US has long rejected efforts toward Palestinian self-determination and subverted international law as well as UN principles to resolve the question of Palestine. Instead, the US has used insidious mediation efforts to ensure what the writer and philosopher Edward Said has called Palestinian “surrender and perpetual subservience” to Israel.

The continued sidelining of international law and the UN as main avenues for Palestinian liberation and the scuppering of an Iranian-Saudi regional deal strengthen the hand of resistance forces in Palestine and regionally. Lebanon lies at the center of this regional resistance to Israel, and Hizbullah is sitting at the center of Lebanese politics.

The “great war” the Lebanese have long spoken of will not be far off. Until then, the UN and its peacekeepers still have an essential role to play in Lebanon, but only after a ceasefire is instituted in Gaza.

Karim Makdisi is an associate professor of international politics at the American University of Beirut and a co-editor of Land of Blue Helmets: The United Nations and the Arab World (University of California Press, 2017)