Emily Tamkin

New Statesman / July 9, 2020

After Netanyahu’s embrace of Trump and annexation, the case for change is gaining ground among US Jews.

“I’ve had people tell me, ‘Things have shifted more in the past two weeks than I’ve seen them shift in the past ten years,’” Emily Mayer said.

Mayer is the co-founder and political director of IfNotNow, a movement led by young American Jews and dedicated to ending “our community’s support for the occupation”, and she was referring to what feels for many like a sea change in Jewish American politics — specifically regarding US policy toward Israel.

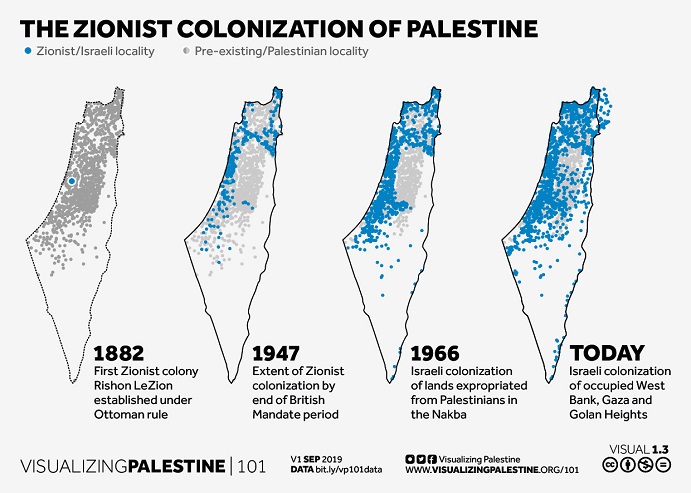

Over the past few weeks, with the threat of formal annexation of parts of the West Bank looming, and the creeping acknowledgement (or long-held recognition, depending on the individual) that Israel has informally taken over that territory regardless, there have been significant shifts both in Congress and in the Democratic Party.

Chuck Schumer, a Democratic senator from New York, and Benjamin Cardin, a Democratic senator from Maryland, both Jewish, came out against annexation — which is to say that two traditionally “pro-Israel”, mainstream Democratic politicians pushed back, however slightly, against Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

Twelve senators also signed an amendment put forth by Chris Van Hollen, also a Democratic senator from Maryland, that would prohibit US defence assistance from going toward annexation. Those who signed on included Bernie Sanders of Vermont and Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, both of whom ran for the Democratic presidential nomination, ultimately losing to Joe Biden.

Meanwhile, in the House, Congressional Progressive Caucus co-chair Pramila Jayapal and progressive star Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez started a letter that called for conditions to be placed on aid to Israel – an idea that, per a 2019 study from GBAO Strategies, actually has support from a majority of Democrat voters.

The American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC) has objected to both the amendment and the letter , arguing they contradict the ten-year security assistance Memorandum of Understanding the Obama administration reached with Israel. Some have noted a certain irony in this, however, given how critical AIPAC was of Obama when he was actually in office.

At the same time, various groups composed of young Jewish Americans signed onto letters demanding that the Israeli government be held to account. Over 1,000 alumni of J Street U — the university branch of J Street, which was founded roughly a decade ago as the “pro-Israel, pro-peace” alternative to AIPAC — signed a letter that argued, “Only when Israeli leadership feels that doing so will jeopardize a portion of its $3.8bn in annual American assistance will it have a real reason to reconsider”.

IfNotNow’s petition from Jewish Americans to Jewish progressive politicians read, “I am calling on you to help develop and support legislation to ensure that US funding is used to move towards preventing annexation and achieving freedom and dignity for all Palestinians and Israelis — and does not fund any activities of annexation, such as home demolitions or building additional Jewish settlements in the Occupied Territories”; it garnered over 1200 signatures.

Peter Beinart, a leading Jewish commentator and author of The Crisis of Zionism, wrote a piece in Jewish Currents and then another in the New York Times arguing that the two-state solution is dead, and that attention must now be turned to establishing one binational state with equal rights. This is not a new argument; Palestinian activists and authors have been making the case for years. Nor does the fact that Beinart made it mean all Jewish Americans now accept it; Daniel Shapiro, Obama’s ambassador to Israel, came out strongly against. But to have Beinart admit that he was crossing over a previously respected red line out of concern for the reality on the ground and human rights did feel new.

There is, then, a change. But is the change coming from the top down or from the bottom up? And how significant will it actually be?

Mayer, who is herself part of one group trying to push for change from the bottom up, credited certain politicians for working to resist business as usual.

“I think the conversation about what is sound policy toward Israel-Palestine has been in part driven by progressives within the Democratic Party”, she said, pointing in particular to Sanders and Ocasio-Cortez, and adding, “I don’t want to underestimate the significance of the ways that they’ve shifted what has seemed possible in a very short amount of time by bucking the status quo”.

Others suggest that top-down change has come not only because of what progressive politicians have done, but also because of the ways in which conservative leadership has conducted itself.

“Top-down [change] has been from Bibi Netanyahu in particular”, said Ilan Goldenberg, Middle East security director at the Centre for a New American Security. Goldenberg pointed both to Netanyahu’s “very bad relationship” with Barack Obama and the “Bibi-Trump lovefest”. Roughly 70 per cent of American Jews voted against Trump in 2016 – that Netanyahu so closely embraced him, and that Trump so openly defends Netanyahu’s policy, has opened up space for liberal Jewish Americans who were otherwise defensive of Israel to question its behaviour.

“Bibi has made the calculation”, Goldenberg said, “that most American liberal Jews are assimilating, they can’t be counted on, [instead] it’s going to be the evangelicals and Republicans and modern Orthodox Jews.” That is to say, the calculation of the Israeli leadership, per Goldenberg, is to “let go” of most American Jews and turn to these other groups for support.

“I think that’s a terrible calculation”, he adds, noting that Netanyahu has done more to convince his parents that Israel can be critiqued than anything he, Goldenberg, has said to them.

Goldenberg also credits “younger people who are growing up and see the Palestinian issue through a human rights lens”. They see it as a civil rights issue, much as they see, for example, the case against police brutality and systematic violence against Black people in the United States. This, it should be noted, is, again, a parallel that Palestinian and Palestinian-American activists, thinkers, and writers themselves – such as Yousef Munayyer, former executive director of the US Campaign for Palestinian Rights, writing this week in the Nation – have made.

Younger Jewish Americans don’t necessarily see Israel the way that older generations of American Jews saw it, as an underdog surrounded by hostile states surviving despite all odds. That, Goldenberg said, is “the old paradigm” – and the shift “has been very bottom-up”.

Even with top-down and bottom-up reasons to change, and even with letters and amendments and essays, Democratic policy toward Israel, much less US policy toward Israel, won’t change overnight. Biden, as candidate and potentially as president, will be slower to press for a change in course than, perhaps, Sanders or Warren would have been. And while an amendment by one senator that managed to get 12 others’ signatures is something, it’s not enough to enact legislative change.

Still, Goldenberg said, “Everybody’s moving”. Beinart is in a different place than he was a few years ago, and more liberal Jewish Americans are now where Beinart was a few years ago.

“Things are moving. Things have been moving and will continue to move. We’re in the middle of it,” he said.

“The youngest are the ones who are pushing the hardest,” he said, “but the evolution is happening everywhere.”

Emily Tamkin is the New Statesman’s US editor